INTERVIEW WITH ALLEN FRAME FEBRUARY 2021

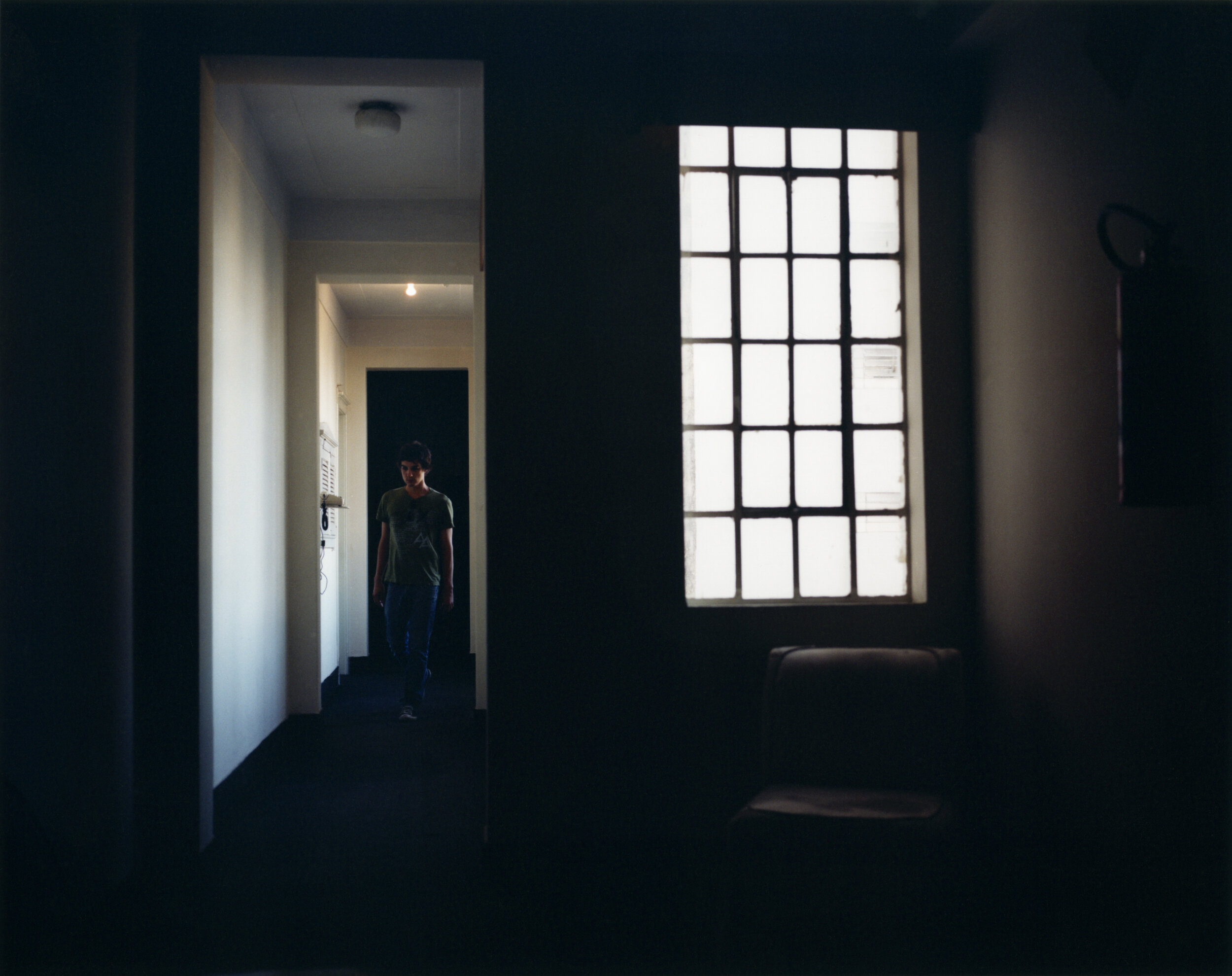

STEPHEN FRAILEY: It is tempting to consider your black and white work as so very different from the newer use of color material, and the textures of each group are quite pronounced and contribute dramatically to their separate moods. But, on the other hand, there is such a consistency in all of the work; the choreography, the melancholy, even foreboding. Is this correct?

ALLEN FRAME: Yes, I think the black and white work from “Detour” (2001) and the color work from 2007 forward are very related in terms of content and approach, but given the span of time, there are shifting moods. This direction, of photographing my own context of friends, came from the start in Boston and then in Mississippi in the Seventies, but became more like the later work when I moved to New York in 1977. I was back in an urban setting then, like Boston, but more consistent. The more recent color work is of people I know but in international locations, and not always so urban.

What IS very different, though, is the work from the last three years where I use found photos, drawings, and paintings, and include my own photographs and texts with them. Instead of photographing strangers, I'm using found photos of strangers and imagining narratives that connect them. Some of these pieces have over fifty individual images; others are much smaller. I did a few simple pieces like that earlier, where I combined my work with found or appropriated work in simple diptychs with text. In the mid-‘90s I made a series called ‘Buddy and Frank’ in which I paired images of my Mississippi mentor's photos of his boyfriend in the 1950s with photos of my long-term boyfriend Frank. They are paired according to situations: boyfriend reading a book, boyfriend on vacation, boyfriend in the mirror. I have wanted to get back to that way of working for years but could do it only recently, when it's taken such an unexpectedly elaborate form.

SF: Your phrase imagining narratives to describe the use of the found images could, perhaps, also be considered in relation to all the work? The photographs you have made, whether the early black and white or later color, seem to quite purposefully suspend the narrative….

AF: I'm aware of the pitfalls in dealing with narrative in visual art. Using it too directly can create sentimentality and melodrama. A lot of the modern and contemporary narratives I'm most interested in, whether in film or literature, are thin on plot; their narratives are less plot-driven than steeped in mood, atmosphere, psychological contemplation, and autobiographical reference.

In my photographs there's an inherent reality that we see, real people in real situations, not actors in a film or play that I'm directing or writing. I acknowledge that reality, but of course, I shape it, with various decisions of framing, editing, sequencing. I want to acknowledge my subjectivity, too, my projections onto people and situations. What is exciting to me is the mixture of the two, the coming together of some "objective" reality and "subjective" experience. I title images with the actual subjects' names, the actual location, the actual date, but what seems to be going on in the photograph may not reflect the actual circumstances.

"Personal documentary" came to be a general term used to describe this kind of work in the Seventies, but since "documentary" itself was never specific enough, "personal documentary" also doesn't accurately suggest the kind of psychological intimacy, or psychological abstraction, that I'm going for. In the new pieces I'm making with found images, there is that basic reality in the work--- pictures of real people in real locations. I acknowledge that with titles that reference their names, but the work I add to it, my pictures of people in the present, suggests the fiction that the people in the present are related to the people in the vintage found pictures. They appear to be their descendants. These overlaps are interesting to me. We all live with myths, some familial, some societal, and those myths impinge upon us as we create; no matter what our purported stance, those myths, biases, assumptions etc affect how what we photograph manifests.

SF: This makes me think of stills from an improvisational film or theater piece, and of course stills have no dialogue, an important part of narrative. Could you please talk a bit more about your relation to theater and writing for the stage?

AF: Something I was getting at was about subtext. I was watching an interview last night on youtube with Mike Nichols, who was on my mind because I've been reading Philip Gefter's bio of Avedon, and Nichols and Avedon were close. One thing he said about directing was how different what is happening in a scene is from what is being said.

I lived in London from 1985-87 and was writing about experimental theater for a Japanese magazine and co-writing a play with Bertie Marshall, which I then directed. When I came back to New York in 1987, some of my close friends had come down with AIDS, and the whole downtown scene was devastated.

I wrote, directed, and performed in a few autobiographical, experimental theater pieces using projected photos, but I gave it up and went back to photography.

I then didn't do any more theater work until around 2011, when I started writing a play about my family as a dramatic situation was happening. I just took notes for a year and finally started writing the play and by 2014 was beginning to have small private readings with actors. The last reading I had was a year ago. I was lucky to have the same great Southern actress through all of them. Jane Welch played the character based on my mother, a huge role. My mother and older brother inspired the two main characters. Since I started writing it, both have died. It's called “Dogs Barking in the Deep South”.

Initially, I was more interested in directing, and most interested in experimental theater. But I was torn because I was also very interested in playwriting. In the ‘80s my model was Maria Irene Fornes, who wrote and directed her own plays. And after directing the play I co-wrote with Bertie in London, I wanted to direct my own work, not someone else's, but I wasn't ready to write. Now I'm interested in writing and not directing. Over all these years, I've followed theater in New York and paid attention to an important generation of younger playwrights, such as Christopher Shinn, Annie Baker, Robert O’Hara, Dan LeFranc, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, David Adjmi, Jeremy O. Harris, and Lucas Hnath, and I co-produced Joshua Sanchez's film “Four”, adapted from Shinn's play.

The work I did in theater in the Eighties, though, really influenced my photography in the ‘90s. I had been more influenced by film initially, but the experience directing in theater made me think more about figures in space. The proscenium created another kind of frame.

SF: Let’s circle back a bit. You mention "mood, atmosphere, psychological contemplation, and autobiographical reference” of the contemporary narratives that interest you. What are they in your work?

AF: There's a sadness and resolve, the desire to keep going while feeling pain, disappointment, etc. There's an ambivalence about the moving forward, a sense of alienation, loneliness, and there's also a strong sense of attraction. How do love, desire, and eros mitigate feelings of sadness and alienation? How much does companionship or love mitigate a sense of futility? What is the tension between someone's sadness and their vitality? What does a certain style and glamour mean in all this?

SF: It is a poignant and profound inquiry, particularly in the relation between eros and melancholy. And to your point that was suggested by the Mike Nichols reference, the feeling runs below the surface of the picture. It’s like walking into a room and being aware that there is an exchange of strong feeling between those there, but without knowing any details….

AF: Thanks, Stephen. Mark Durant has included my picture of the swimmer in a pool at night in Mississippi in his new book “Running, Falling Flying, Floating, Crawling”. The text on the opposite page by Leslie Dick talks about her early memory of being onboard an ocean liner and participating in a lifesaving drill, and later, of having recurring dreams of being in the sea among tall waves.

I remembered that my own first memory was of nearly drowning in a swimming pool, floating suspended underwater before my mother jumped in with all her clothes to rescue me, and I'm thinking about how that early experience of near drowning led me unconsciously to making this picture. I had met the guy at the gym. He had mentioned that he had a swimming pool and invited me over. I asked him to let me photograph him in the pool. Some people have asked me whether it's a self-portrait. I think that the pool situation is from my childhood----my mother was a swimming teacher, and I spent the summers in swimming pools. But the "noir" element is my interest in this guy's dark stories of seducing people by inviting them to his pool, and his collection of nude Polaroids of them, one of whom turned out to be someone my mother taught to swim. Efrem Zeloni-Mindell has also included this photograph in his new compilation, Primal Sight.

SF: There is a strong romanticism in your work that is unexpected because of the grisaille, the grain of the photograph. Your use of the word ‘noir’ is useful understanding the subtext of darkness in the work, perhaps a dread that is also quite thrilling. Is much of your work consciously based on memory?

AF: Memory, no, not consciously, just intuitively. Interesting that you reference romanticism and film noir both because film noir comes from German Expressionism, and I relate more to that than romanticism.

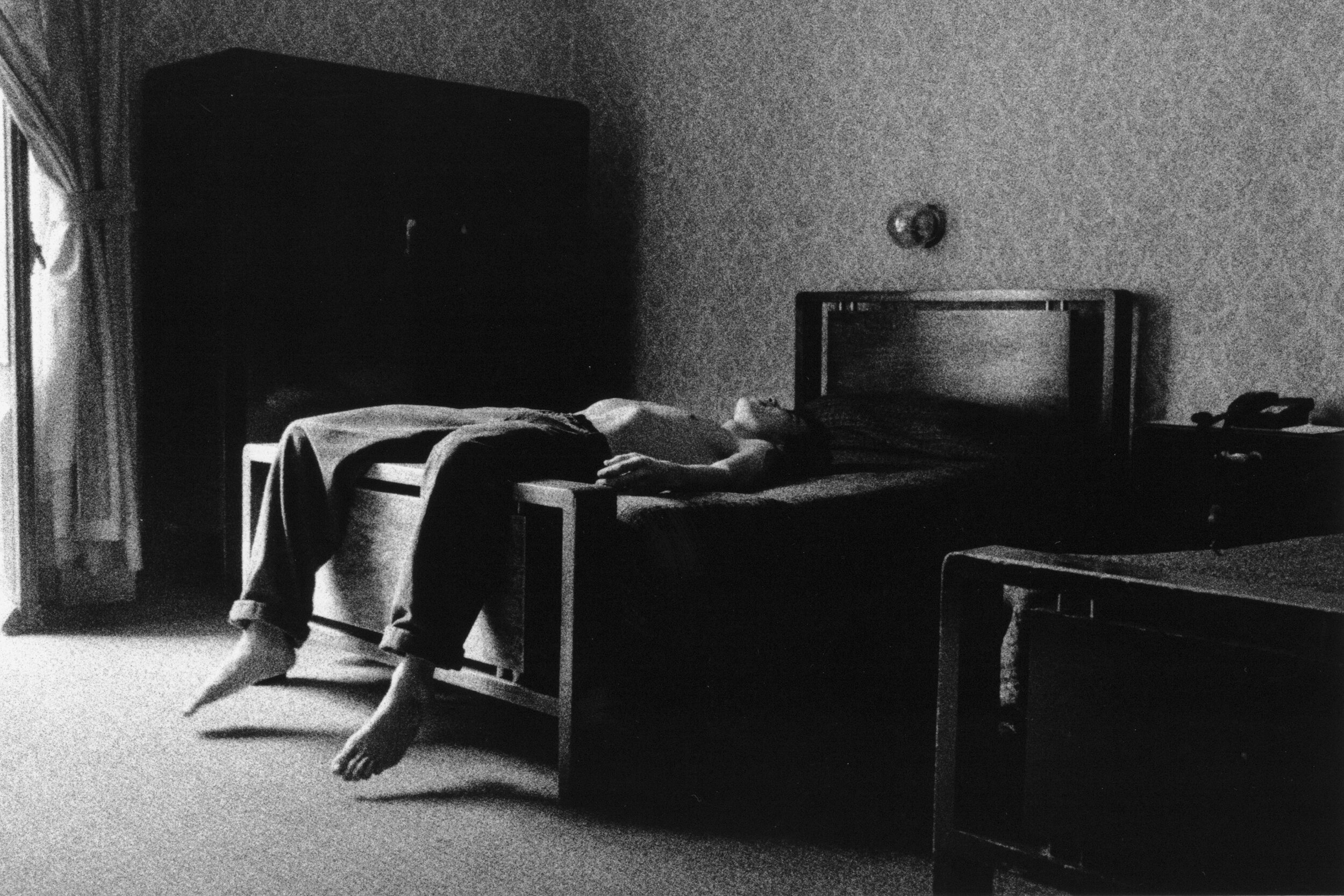

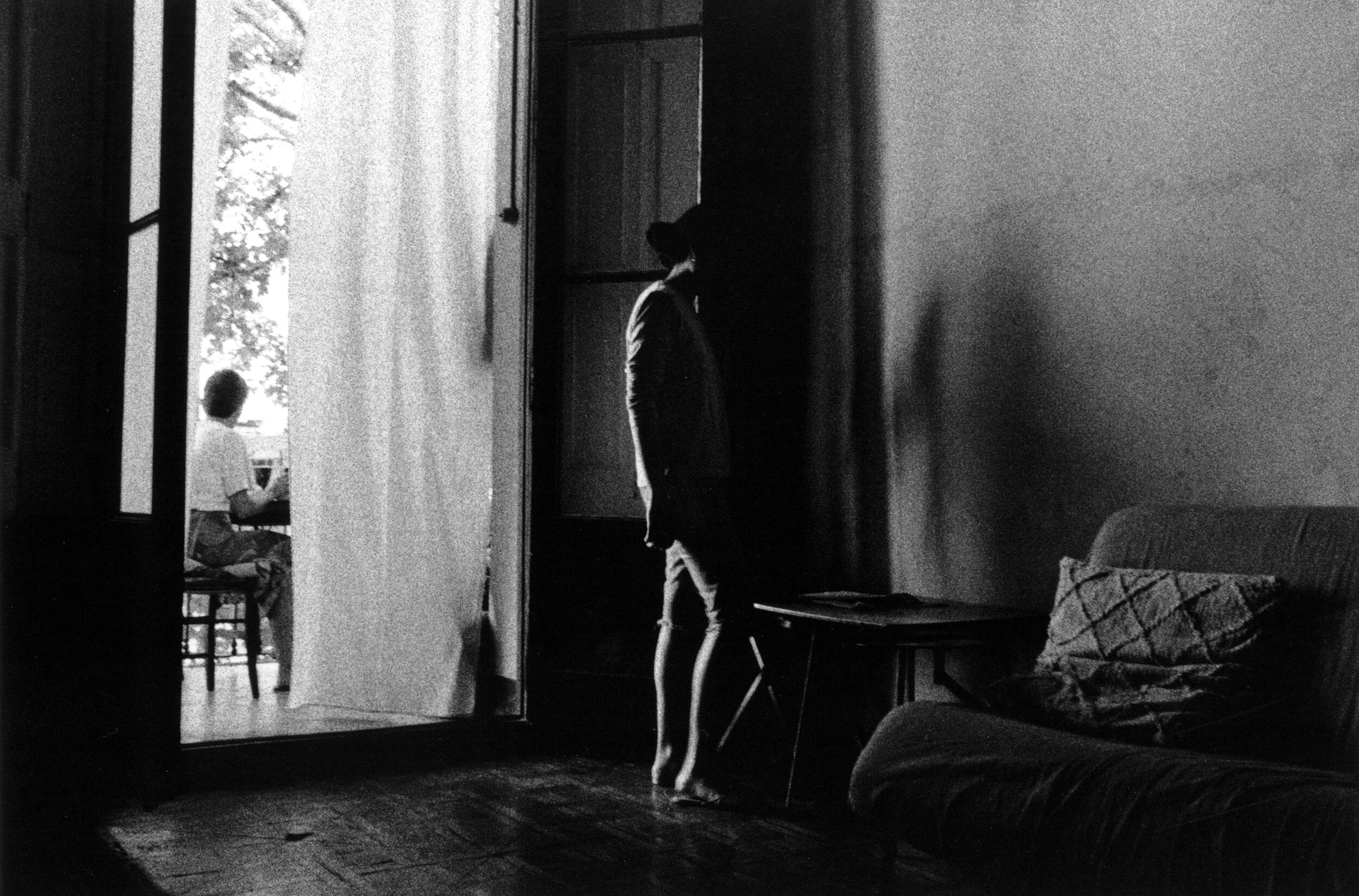

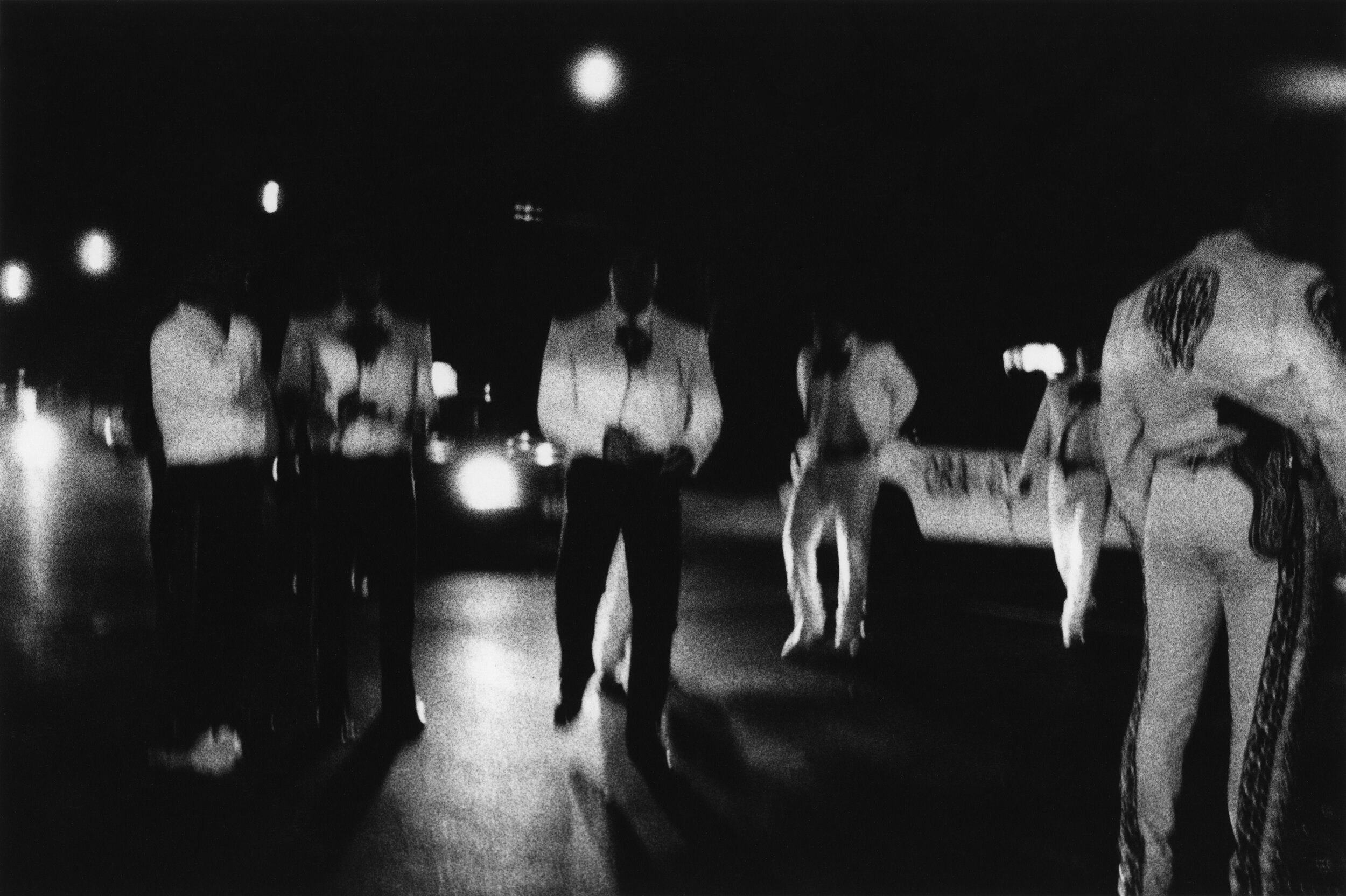

The grain came about when I started using, and pushing, high speed black and white film from the late ‘80s in order to be able to photograph in dark interiors without using artificial light, which I had been avoiding since the use of on-camera flash in some of my pervious Boston and Mississippi work. Occasionally, I used it even when I was outdoors in bright light because by that point, I wanted the look to be consistent. I allowed the grain as a kind of raw contrast to the increasingly “composed” or stylized images I was making. I never set things up or arranged the scenes, but sometimes they look so precise that a viewer might think I had. And in that period, photographers were doing a lot of staging, so I felt I had to point out that they were unstaged and unposed in my statements.

My technique was kind of like that of a street photographer using a 35mm camera shot with very fast reflexes, even when the scenes look slow and still. These pictures from the Nineties are influenced by my work as a director in theater, seeing figures in a room but almost as if they were on a stage. In the earlier photos that was less the case. You can see where I was going for some sense of mise-en-scene in space, influenced by cinema, using foreground and background, spaces split by walls or figures, but I was working with New York City apartment space mostly, which is tight, confined, more difficult to photograph in than later spaces I would find in Europe or Mexico.

Someone once compared my work to Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans’, and I was kind of nonplussed by what I thought of as a random, irrelevant comparison, even if I was flattered to be compared to Frank. His Americans were strangers in public spaces; my ‘Detour’ work was people I knew in intimate interiors. I thought about that comment a lot, though, and realized that in using 35mm, I was using a classic photo approach, but the content was subtly queering that canonical work. It was not an “on the road” tour but I was traveling a lot. The locations are foreign, even if interiors, and the content, though captured in a classic reportage mode, was often homoerotic and connected to the queer experience and yearning of the photographer.

Regarding the “romantic” in the 1981 color work, what has struck me about that time photographing was the irony of our innocence and hopefulness on the cusp of the AIDS pandemic. In retrospect, the carefree attitude seems naïve. The daytime palette in color emphasizes that innocence. I was happy and joyful in making that work, having found a like-minded community of other creative gay and straight friends in New York. Still, there is a pensiveness to a lot of the figures in that work, even when they are seen together. That pensiveness, the state of mind of being lost in reflection or yearning, may suggest the sense of awe expressed by figures in Romantic painting tropes, but it’s not awe they’re expressing, or surrender to the sublime. It’s more the moments of self-questioning, psychological introspection, hints of doubt or alienation, even in the midst of social encounters. I was coming from spending a few years in Mississippi where I was photographing a kind of marginal, gritty, underground gay scene that revolved around a transgressive alcoholic gay friend who wound up in prison and was one of the first to die of AIDS. I felt relieved after that to get to New York, which felt safer, affirming and less disturbing.

Painting, which has been theorized much more rigourously than photography, has its periods, from Romanticism to Realism to Modernism, etc, but those broad movements don’t fit onto photography that neatly, especially when you take into account the influence of cinema and literature on still photography. If I acknowledge, for instance, the abstracted psychological narrative of Antonioni in “La Notte”, his framing, his tenuous connection to plot, as an important influence on my own later still photography, or talk about how much I relate to the narrative style and content of Roberto Bolaño, especially in “The Savage Detectives” where he is portraying the hedonism and interconnected lives of his young poet characters in Mexico City in the ‘70s, how does one locate these points of influence and dialogue in the art history of photography? Talking about “the Boston School” vs. the “Pictures Generation” in American photography, Modernism to Post-Modernism, is a shorthand but inadequate. We have overly broad categories derived from painting’s history, but photography as a medium is more of a hybrid and has as yet not attracted the same kind of rich analysis as painting.

SF: Indeed, art historians and photo historians alike seem inclined to bookend, but isn’t that a shorthand for shared characteristics and influence and motives? But to your point, photography feels like the most absorbent of mediums, perhaps because of its immediacy, sponging from literature, cinema, popular culture, daily life. That is one of the things I find so appealing about it. Maybe this is also part of your engagement with the medium (rather than theater or literature): its capaciousness, its democracy, the fact that all of your disparate interests can feed the work.

AF: Yes, it's a handy shorthand. I would love to see more writing about this hybridity. I have come to photography with the skills of a writer and wish I also had the skills of a painter or sculptor, or had taken the time to develop those skills so I could use them with photography. I would love to see more writing about this hybridity.

SF: As an artist, I’m often struck by how one’s work reveals itself over time, one discovers new things about work they may have made years ago. It can be quite exhilarating and reassuring. Is there anything that you have learned about your work recently?

AF: The fun part is learning how my early work speaks to a younger generation. It's exhilarating to discover that early work that seemed so much a part of my past has a new life. I want to hold on to that feeling, to use that encouragement to keep producing and to fuel the daunting project of getting my archive in order.

All images courtesy Gitterman Gallery, New York.