JEAN DYKSTRA

There’s a fairy tale quality to Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s photographs that I’ve always loved, from the deeply weird and wonderful Family Album of Lucybelle Crater to his photographs of his own actual family, in the fields and woods around Lexington, Kentucky, where he lived. I’m not thinking of the happy-ever-after Disney versions, though, but rather the original 19th-century stories by the aptly named Brothers Grimm. In their telling, benevolent creatures are regularly transformed into something sinister, and children are repeatedly left in the wilderness to fend for themselves. Beautiful in their way, these stories also draw on some deep, archetypal anxieties.

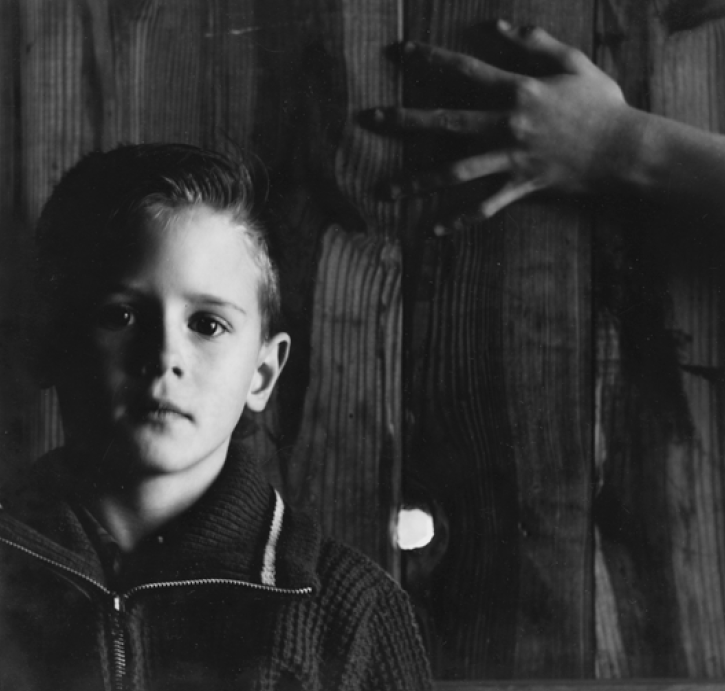

Meatyard’s photographs of his children, part playful family snapshot and part horror film, have a similar quality. When he was asked what kind of feeling his photographs were meant to elicit, Meatyard famously said he hoped it was something “akin to a shiver, and as pleasurable as a shiver sometimes is.” This photograph, of Meatyard’s young son Christopher, embodies all of the unsettling contradictions that make his pictures so powerful. There’s the boy’s beautiful face, gazing directly out at us, all fresh-scrubbed innocence. And yet: his expression is inscrutable, and maybe a little knowing, as if he has the full measure of this mysterious situation. Meatyard has photographed his son’s face half in shadow, half in light, seeming to suggest the possibility of his dual nature. Then there’s that grasping hand behind him, and that perfectly round hole in the wall of the barn, a punctuation mark hinting at some indeterminate act of violence. (I’m assuming it’s a barn, because Meatyard took many photographs of his wife and children in and around dilapidated barns that he came upon on long drives near Lexington.) What strange, southern Gothic situation do we find ourselves in here?

Meatyard himself was something of a contradiction: born in Normal, Illinois, he was anything but. He was an optician who frequently blurred his photographs, and a family man who enlisted his wife and children in creating disconcerting scenes for his camera. There was a period in the 1990s when the term “uncanny” became the most overused word in art criticism (I’m sure I was guilty of it), but I’m tempted to use it here. It gets at the Freudian sense of something at once frightening and familiar at the heart of this picture, which gives me a shiver, a pleasurable one, every time I look at it.

RALPH EUGENE MEATYARD "Untitled", 1961.