By Jessica Shearer, February 10, 2025

A decade before he cemented his reputation with The Americans, Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank was a lovelorn 25-year-old snapping shots of Paris and arranging them in a scrapbook alongside observations for his soon-to-be first wife, artist Mary Lockspeiser.

It is this earlier iteration of Frank one finds in “Mary’s Book,” on view at the Museum of Fine Artsin Boston on view until June 22. Exhibiting the book with forty-eight gelatin silver prints, the show is something of a held breath, an exploration of life’s interludes, those potent moments we recognize only in hindsight.

Here it’s the case of suspended love in a city just starting to recover from the war. Having only recently met Lockspeiser in New York when he set off to Paris in 1949, Frank found everything—from chimney-crowned roofs to innumerable waiting chairs—redolent with potential. “The simplest things change if a man comes into contact with them” he scratches onto a page, “even a pissoir.”

The book is a simple handmade thing of folded paper and is held within a vertical column of glass, a floor-to-ceiling vitrine situated smack in the center of the small room. It is exhibited in separate spreads so viewers can circle it and take in its entirety. Two stand-mounted screens allow visitors to flip through the pages digitally, zooming in on details and making use of translated text. Frank’s notes to Mary are primarily in French while sprinkled with the odd English phrase.

In the show’s single room, identically framed photographs are hung mostly in two rows, pseudo-salon style. It would be a mistake to assume that the prints are an alternate display of the book, or that the volume is simply a collection of the works on the walls. For all of its delicacy, the book contains more images (74) from his first five months in Paris, while the bulk of the show covers 1949-1952 and another wall explores Frank’s later photographs from the sixties and seventies.

Still, there’s a significant amount of overlap, and in the prints one can better appreciate a cocked eyebrow or a child’s grin while gaining a glimpse into the artist’s process—some of thembear crop marks and comments—though they can’t capture the endearing quirkiness of the book. Part of this comes down to simple presentation: on the page, Frank can play with similarities and contradictions. One spread contains an avalanche of shots from a single street while another juxtaposes tone and shape. In the left of one such spread, a man sits forlornly at a transit stop, the raking light sending the slats and shadows of the bench shooting off to the right, landing in the fold and establishing the height of a smaller shot on the next page. It’s all right angles and exhaustion. Opposite, a man holds a raft of balloons bobbing in joyful, globular anticipation. Such stark contrasts are more difficult to perceive on the wall, as images inevitably absorb the tenor of the photographs surrounding them.

Perhaps this is why, while Frank’s pages feel so intimate and immediate, the show can’t help but sink into a more collective nostalgia---the soft-focus sweetness of the earlier photographs heightened by light grey walls the color of Parisian skies and the artist’s moody scrawl quoted in black vinyl on the wall “From the Eiffeltower. Arc de Triomphe. everybody photographs the Eiffeltower (sic).” In the book, the distance Frank perceives between himself and the average tourist is palpable; the detachment fades into something more resigned when you find the phrase again on the wall.

Still, what we’re talking about here—whether private desire or emblematic romance—is love, the concern contained in the quotation Frank uses on the cover page of Mary’s Book. From Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince, the order of its sentences has been swapped: “What is essential is invisible to the human eye. It is only with the heart that one can see rightly.”

Frank will use this quotation (in the original order) to kick off his next book—his first for the public—Black White and Things. And it’s in this corrective repetition that we find what is wonderful about shows like “Mary’s Book,” which perhaps don’t show an artist at the height of their powers, but which does see them agitating like an oyster on their bit of sand, refining preoccupations that—having been tested on lovers—are ready to be issued into the world, bright and gleaming as pearls.

Jessica Shearer is an art-writer and critic and is a Senior Editor at the Boston Art Review.

ROBERT FRANK, spread from Mary's Book (detail), 1949 © The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation. Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

ROBERT FRANK, Paris Diptych; "Balzac Helder Scala Vivienne" poster, 1949 © The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation. Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

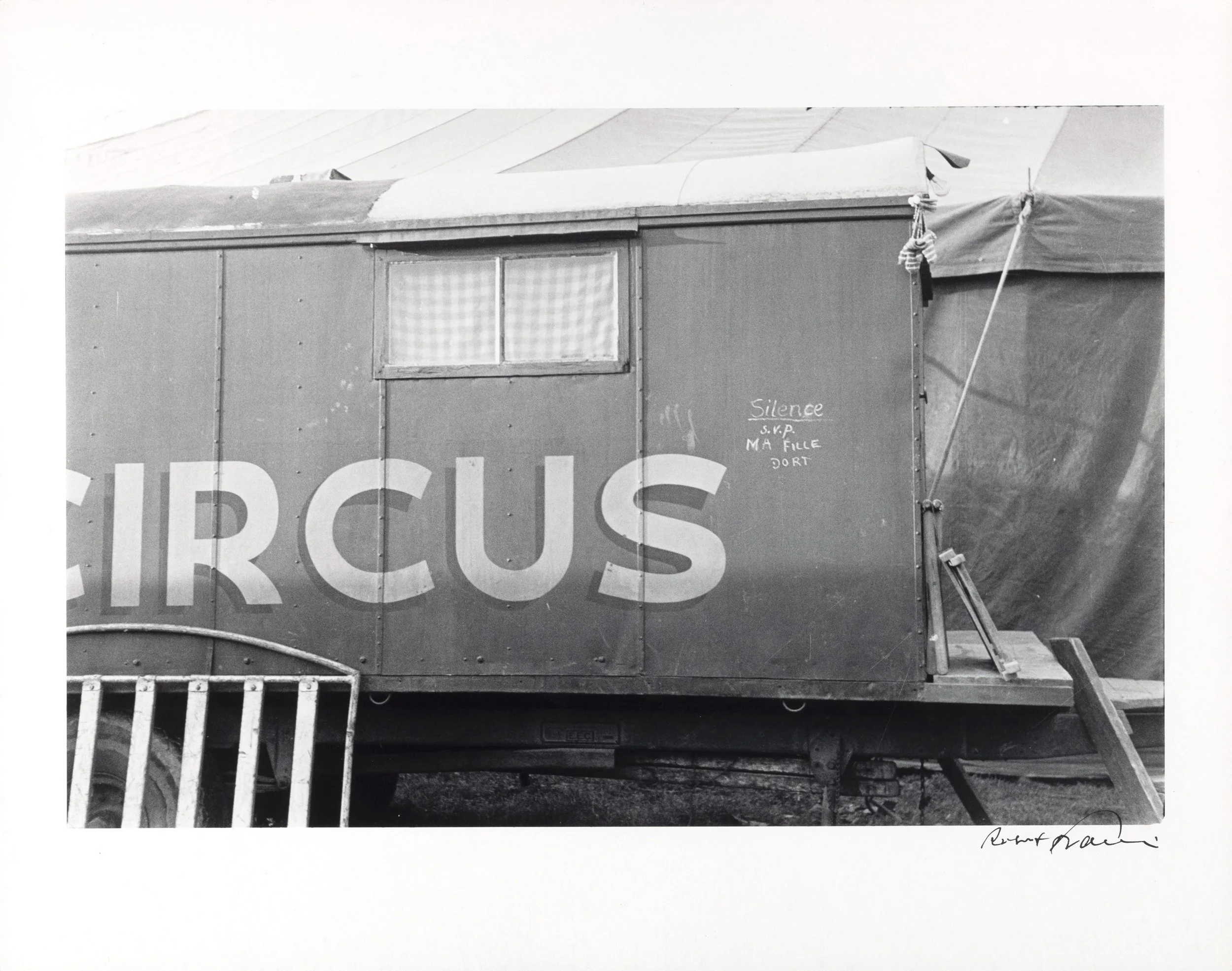

ROBERT FRANK, Trolley car with "CIRCUS" painted on side, 1949 © The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation. Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston