By Alexis Clements, February 10, 2025

One of the large black and white photographs hanging on the wall is titled “I photograph my dad through his window. Leverett, Massachusetts, 2018”. The only reason we can see the face of Alice Proujansky’s father, Jed Proujansky, is because the dark reflection of Alice’s hair and camera interrupt the otherwise bright image of the sunny yard on the pane of glass that separates parent and child. It is because of her own shaded figure in the frame that we see him. The evocative layering and refracting of one generation through another, pushing foreground and background into one another in ways that merge and overlap, is a gesture that repeats both in the monochrome photographs, as well as the book that accompanies the exhibition, “Hard Times are Fighting Times”, now on view until February 26.

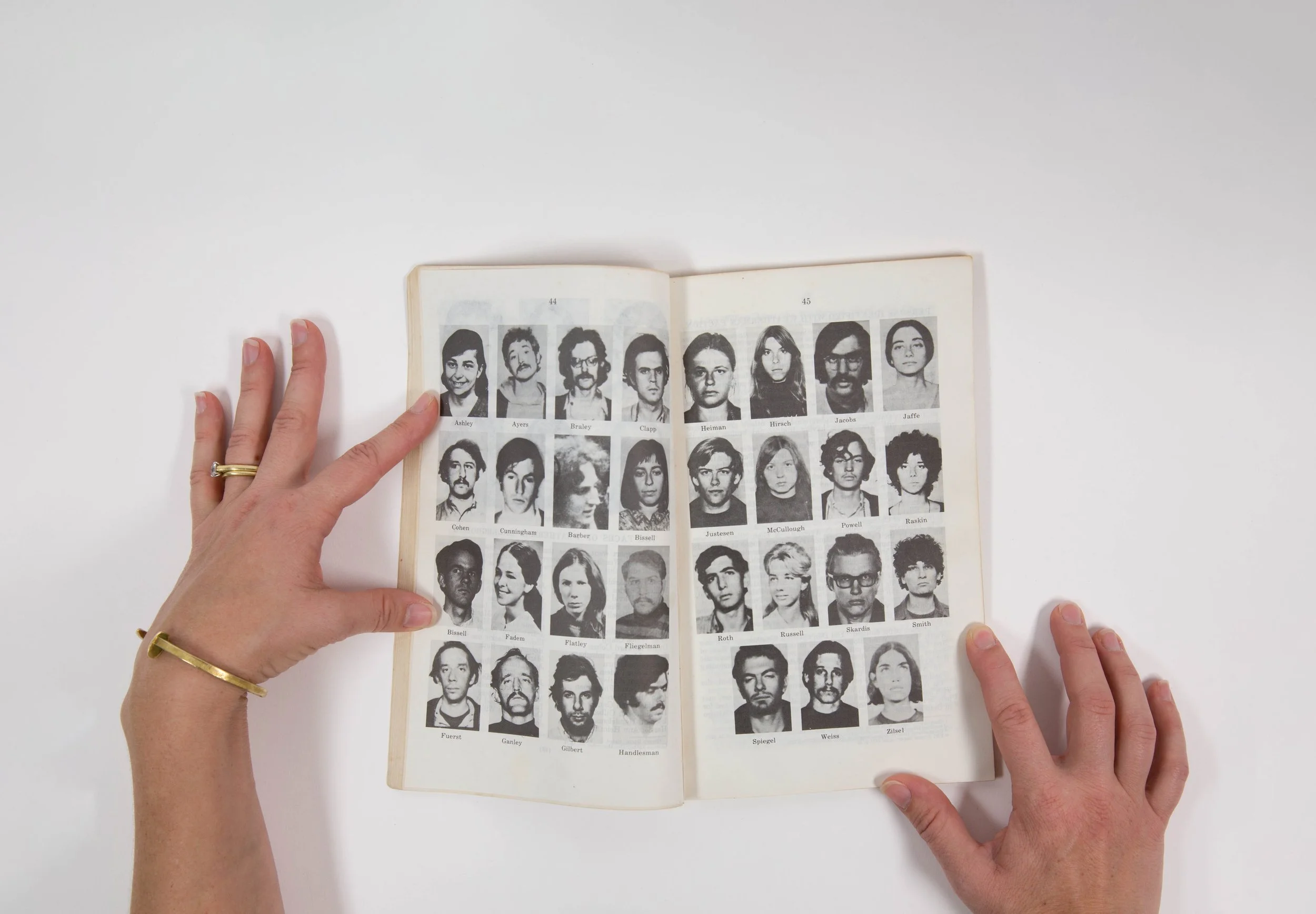

This richly documented project by photographer Alice Proujansky consisting of her original photographs and archival material, focuses on the political history of her family and feels particularly relevant as we now enter a new chapter of upheaval in the United States. Proujansky’s father and mother were both active in far-left political movements of the 1970s. Jed played a role in the earliest years of the Weatherman, a militant anti-imperialist group who came into the public consciousness in 1970 when The Weather Underground thus undertook a series of bombings aimed at inciting revolution against the U.S. government. And he met Alice’s mother Joan Deely in 1976 while Joan was working with the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, the aboveground wing of the organization. The two eventually left the Weatherman and went on to work with other groups such as the Native American Solidarity Committee. And, of course, they eventually started a family that came to include Alice.

Under the heading “Mother’s and Father’s Ambitions for Baby” in a baby book Jed and Joan kept for Alice is a single handwritten entry dated November 1980: “To grow up and be anything you want, except a fascist or a banker”. Looking back from today’s vantage point, it’s a line that reads with humor, but one that also evokes the deeply felt slogans and declarations embedded in the other archival materials that Proujansky photographed. In those images we see the book cover for “Outlaws of Amerika: Communiques from the Weather Underground”; we see a flyer calling for activists to support the case against the police officers who murdered Black Panther Party deputy chairman Fred Hampton, and political buttons demanding that onlookers “Stop Racism,” “Stop the Bombing in El Salvador,” “Free the San Quentin 6,” and cautioning that “The Moral Majority is Neither.” We see also an aged cardboard box with black writing scrawled on top indicating that it contains FBI files, which Jed obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request in 1975 so that he could know what the government had on him.

And yet, even as compelling and tactile as the archival material is, it is the black and white images of family that pull at something that feels more nuanced, less declarative. Who are you really? they seem to ask, as child gazes onto parent, searching. The search digs deeper in images like “My mom instructs January to water the garden while my dad talks. Leverett, Massachusetts, 2019.” Joan’s arm is raised, her back straightened, her gesture evoking propaganda posters from across history, while Alice’s child January plays with a hose in the grass ahead of her, both overseen by Jed, above them in the background. The image seems to ask us how a life takes shape beyond the slogans. How do beliefs ripple and rupture across generations? How does a radical leftist care for their family, and what does that family become?

Even as the Weatherman have been critiqued for their whiteness and the fact that many of its members came from the middle class, what we see in Provjansky’s family portraits is not a story of privileged rich kids briefly rebelling, only to return to the comforts from which they came. Instead we are given an intimate glimpse of how a lifetime of political striving has shaped this very particular family, and what it has meant to Alice’s parents to try to uphold political commitments not only in the streets, but also in their daily lives. It’s a striking depiction of how public histories intersect with private lives over time, which is something we rarely see rendered, particularly about activists who are not among the most famous or lauded. And it begs the question of why we don’t see more of this, why the idea of being a leftist in the U.S. so often starts and stops with specific political acts. What does the child of a committed revolutionary know that you don’t about the reality of a political life? And what can knowing that the life went on after the upheaval teach us about what it means to take a stand against injustice in moments of crisis?

Alexis Clements is a writer and filmmaker. A regular contributor to hyperallergic, her writing has also appeared in The Guardian, The Brooklyn rail, and Bitch Magazine.

Alice Proujansky, “Milk crate containing materials from my parents' archive documenting their activist work” Courtesy of the artist and Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY.

Alice Proujansky, “My dad directs Will to avoid poison ivy. Leverett, Massachusetts, 2019,” Courtesy of the artist and Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY.

Alice Proujansky, “My dad Jed Proujansky’s redacted FBI file, obtained through a 1979 Freedom of Information Act request, dated 2/2/1971” Courtesy of the artist and Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY.

Alice Proujansky, “My parents celebrate their fortieth wedding anniversary with a potluck for family and friends. Leverett, Massachusetts, 2019” Courtesy of the artist and Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY.

Alice Proujansky, “ Weatherman Archive.” Courtesy of the artist and Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY.