By Evan Moffitt, February 10, 2026

Clouds feel like a minor miracle in England, a country often wrapped in a solemn gray pall. That may be one reason why John Constable paid such careful attention to them. The 19th century landscape painter had a singular ability to endow those accumulations of water vapor with an almost human character, referring to them as “the keynote, the standard of the scale, and the chief organ of sentiment”. To a superstitious type, clouds can be augurs – but even for the sceptic, they are natural monuments by which man’s insignificance might be measured. It’s sheer coincidence that a cluster of Constable’s cloud paintings are on temporary display at Tate Britain concurrently with Doug and Mike Starn’s “A Tragedy of Infinite Beauty”, but the twin brothers and artistic partners just as obsessively invest all-too-human hopes and fears in the sky.

The Starns are not, strictly speaking, photographers, and the exact medium of their exhibition at Hackelbury Fine Art through February 28 is up for debate. Each skyscape on display was photographed and printed digitally onto gelatin-slicked paper, and then coated with varying layers of paint, varnish and wax. The resulting images resemble photo encaustics, though the encaustic here seals the image in rather than providing its ground. It’s a process more akin to underpainting than photographic development – Vermeer used a camera obscura, after all – and, for their variegated textures, the resulting works recall Constable’s plein air “oil sketches”, which hold pride of place at Tate Britain. Patches where the varnish, wax or paint has been applied a little too thickly pull us out of the scene, almost like a glitch or a stain. Many of them have been cut up and stitched back together again, as if to warn us off indulging too much in their splendour. To look at these picturesque groupings of cumulus clouds bathed in golden light and notice a cut down their middle induces an unsettling feeling, almost like a premonition of violence.

Violence is literally invoked in these works’ titles – “Bullet Holes in the Cemetery Walls” (2024), “interrogation II” (2025), “people searching a building after an airstrike” (2025) – though figuratively, it’s nowhere to be found. Instead, the heavenly vistas are meant to invoke what the Starns describe in the show’s press release as the skies’ “sublime indifference” to human suffering. As man wages war, clouds roll blithely by. It’s a rather pat, agnostic observation, which may also hold less water in the age of climate change. Ever more frequently, major social developments converge with atmospheric events, so while the skies remain indifferent, they hardly exist in parallel.

The Starns, born in 1961 in the United States, first gained public acclaim for their contribution to the 1987 Whitney Biennial, where they displayed photo-collages suffused with Gothic romanticism: gnarled, leafless trees and a Renaissance painting of an entombed Christ. There’s a work from that period on display at Hackelbury: “Double Rembrandt (with steps)” (1987-1991), in which the Dutch master, dressed in his iconic feathered cap, has been doubled over to form a kind of talisman which radiates lines of energy out towards the work’s margins and visible plywood backing. It’s a weirdly wonderful work which shows the Starns most securely in their element, one which returns the photograph to its nineteenth-century condition as an object to be handled. The creased paper and impasto patches which break up the sunsets in “A Tragedy of Infinite Beauty” also focus attention on the materiality of the Starns’ luminous images, though the works’ charged titles seem almost embarrassed by that fact.

John Berger characterised Constable’s vision of the English countryside as essentially conservative, a romanticised Eden emptied of rural, working-class life. Berger inspired many Marxist students of art history – myself included – to look at art as a bulwark against fascism. It’s an especially tempting impulse in times like these. But what exactly is gained when our resistance to asceticism hardens into a suspicion of what our own eyes can see? The enjoyment I derive from looking at a Constable doesn’t make me a Tory. True sublimity reaches across the aisle. I can care for clouds whether or not they care for me.

Evan Moffitt has written for The Guardian, The New York Times, Financial Times, Artforum,Aperture, 4 Columns and Frieze. He currently serves as Fronts Editor for The Observer.

DOUG AND MIKE STARN "Double Rembrandt with Steps" 1987-1991.

DOUG AND MIKE STARN "it's a beautiful day", 2025.

DOUG AND MIKE STARN "MTN 621", 2021-2022.

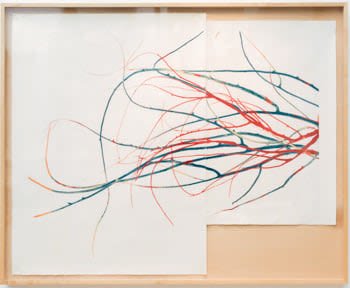

DOUG AND MIKE STARN "Seaweed 3b" 2010-2012.

DOUG AND MIKE STARN "you are my flower, you are my power", 2025.