By Tim Maul, December 10, 2025

Postwar American art would have evolved differently if Robert Rauschenberg, a restless provocateur, hadn’t enrolled at Black Mountain College in 1948 among fellow students John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Arriving from Paris with his then wife Susan Weil, if Rauschenberg was soon unhappy with Josef Albers’ demanding methodology around the applications of color, his introduction to the darkroom by Hazel Larsen Archer at Black Mountain looked in comparison like a natural fit, if not the beginnings of a notable career. The young couple went on to be featured in a whimsical article in LIFE magazine in April 1951 making camera-less blueprints in their tiny apartment and several images were then exhibited and purchased by MoMA in 1953.

Without their identifying wall labels Rauschenberg’s early New York City photographs could be mistaken for the overlooked work of a mature avantgarde insider. A cooperative young Jasper Johns poses with a painting that would change the course of art history hung above an improvised liquor bar. Johns appears again looking dapper in a trench coat and Susan Weil comports herself like a Victorian lady in Central Park. Composer David Tudor occupies a corner of Cunningham’s studio in its Zen vacancy--a feature of downtown loft living. A random light bulb doubles as a comic strip ‘idea’ and reminds of a quintessential blood red William Eggleston picture taken in 1973. Desire fixes Rauschenberg’s gaze on the torso of Cy Twombly on a Staten Island beach. Rauschenberg would continually foreground the camera’s singular ability to flatten the world into two manageable dimensions, stabilizing a Manhattan bristling with signage that the dyslexic artist may have strained to translate. ’Untitled Fulton Street Studio II’ (1953) replicates a section of crumbling wall strongly resembling ‘Rebus’, an important painting from 1955. The pitted interior is bisected by a humble shelf holding an array of tchotchkes--- old bottles, ostrich eggs--suggesting a period bohemian mood board complete with photographs, drawings and even a small Matisse print and a wicker basket. The obvious referent here is Joseph Cornell --who Rauschenberg met while running errands for the Egan Gallery in the late ‘40s—and his use of images papering the insides of his weathered box shrines. Carl Andre, in positioning Cornell, the reclusive Christian Scientist, as the link between European Surrealism and American Pop Art, also inadvertently implicates Rauschenberg in this hybrid.

Although he always considered himself a ‘photographer’ Rauschenberg’s involvement with the medium waned as he reanimated physical found imagery and objects scrounged from his seaport environs. Perhaps the indexical origins of the photographic print were too narrowly nostalgic in his quest for the inclusive ‘real’. While a charming snapshot of his young son Christopher--among the displayed ephemera--would be embedded in a major work like ‘Canyon’ (1959), the floating signifiers of print advertising and photojournalism would separate his collaged paintings and ‘combines’ over the hermetic beatnik assemblages of Ed Keinholzand others. And in the accidental discovery of the lighter-fluid soaked photo transfer, the local newsstand would replace the camera as a source of content; and in the early 60’s Andy Warhol’s silkscreen usage further enabled Rauschenberg to engage with print media. (A usable image for Rauschenberg wasn't all that easy to attain, his 60’s studio assistant painter Brice Marden when asked to select pictures from the LOOK magazine archive only found a single print that interested his employer).

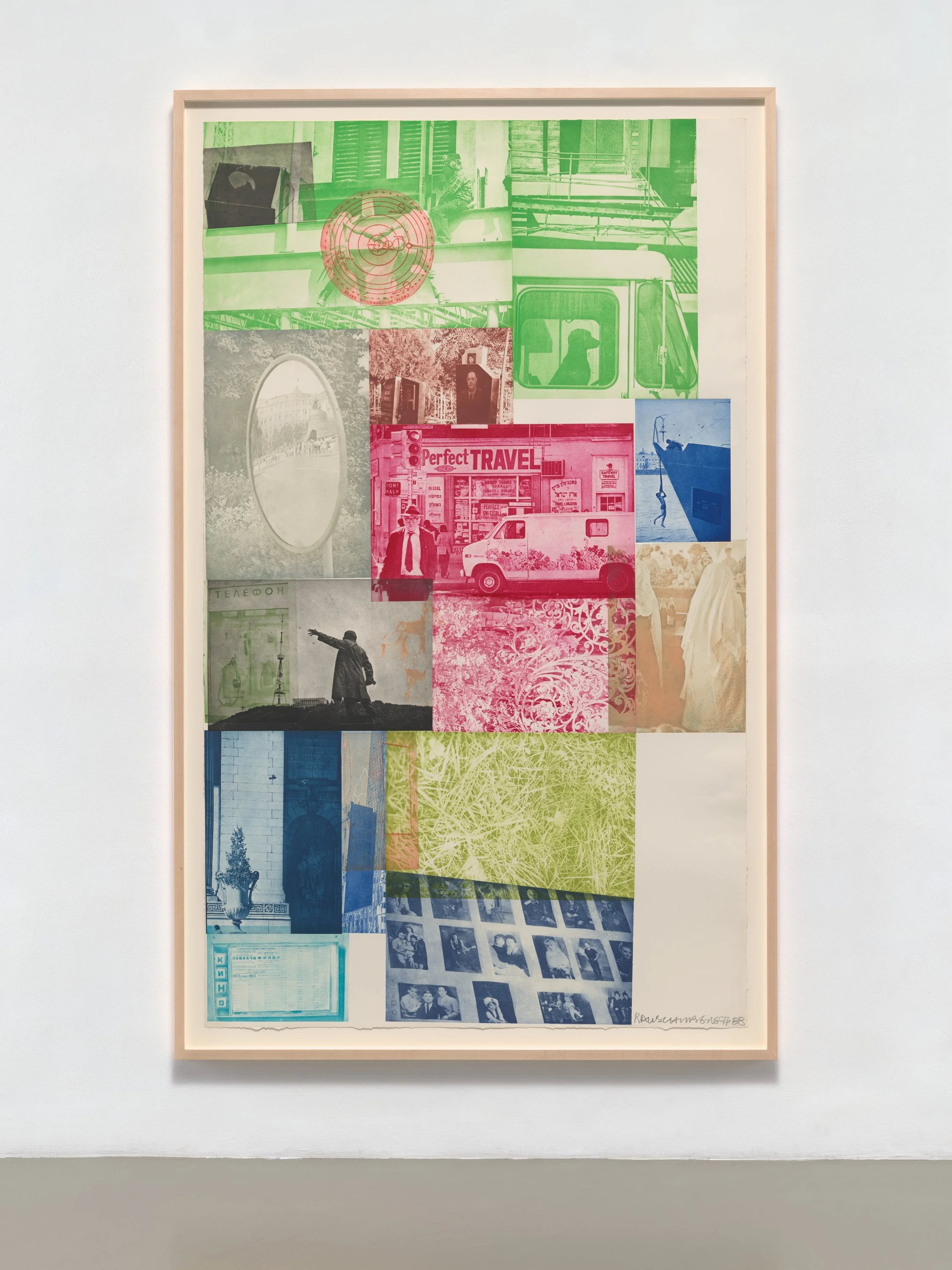

The artist would pick up the camera again and hit the road in 1979 to photograph the United States, a body of work that became ‘In + Out of City Limits’ (1979-81). From that series, 53 prints are included here and often correspond to the influence of Eggleston in addition to Lewis Baltz, a younger photographer who showed regularly at the Leo Castelli Gallery in the 70’s. A homeless man on the Bowery and an American flag with adjacent signage channel Robert Frank’s social consciousness (Rauschenberg’s own commitment to political causes in the turbulent 60’s was considered by some as detrimental to his lucrative studio practice). A looming WTC always startles, and one image of a hotel worker balancing a tray of burgers while ’lady liberty’ looks on is stunning in its relation to this nation’s current brutal persecution of its underclass. Repurposed pictures from this group appear in several small paintings, multiples, and in ‘Photem Series I #15’ (1981) where silver gelatin prints of architectural details mounted on aluminum are grouped into sectional photo-objects. Adhered to the silkscreen Rauschenberg’s photographs serve as templates, their legibility slightly degraded with every application of ink while contributing another layer of private narrative on a variety of surfaces. Pegasus, the flying horse of mythology and logo of Mobil oil, appears first in a photograph and is later screened onto the lower left-hand corner of ‘Wet Flirt (urban bourbon)’ (1994), a sun-drenched mirage of a painting that is central to the exhibition. Perhaps the fantastic beast is ascending, following the arrow to join the dude over on the scaffold----an angel?

I sat transfixed through ‘The Walls Came Tumbling Down’ (1967) a CBS video documenting the making of the ‘Revolver’ series, machines that rotate illuminated plexiglass disks silkscreened with vivid ‘Rauschenbergia’. Hearing Rauschenberg’s voice while watching him deftly wield a squeegee provided a fitting coda to this modest exhibition unexpectedly rich in histories, both his and ours. The final images of both Brice Marden and Robert Rauschenberg were poignant, their faces saturated in color enthralled by this very 60’s contraption orbiting in that fabled gap between art and life.

Tim Maul is an artist and art writer based in New York City and Connecticut. His project around his brother Michael’s (1953-2020) drawings will be hosted by both Leslie Tonkonow Artworks & Projects and Kerry Schuss gallery early in 2026.

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG "New York City Pegasus" 1981 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG "New York City Statue of Liberty" © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG "Sling-Shots" 1995.

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG "Untitled Fulton Street Studio II" 1953 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG "Wet Flirt" 1994 © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation