By Max Blue , December 10, 2025

Alejandro Cartagena’s art is trash – and I love it. The photographer has spent much of the last 20 years documenting cast-off and forgotten places and people. More recently, he’s started working with the detritus of his own photographic process, from collaging to AI assisted, algorithmic sequencing. All of this is on display in the 300-plus pictures in Cartagena’s first mid-career retrospective “Ground Rules,” which runs through April 19, 2026, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Cartagena’s early project “Suburbia Mexicana” documents suburban life in Monterey, Mexico, in the early 2000s. The first series in the project, “Fragmented Cities,” focuses on the failed infrastructure and architecture of the late-‘90s real estate boom, which promised Mexican families the opportunity for homeownership under the new PAN regime. Cartagena shows these new developments then transformed to ghost towns as the cost of living and lack of resources made them uninhabitable. The ruins of the suburban fantasy echo a larger socio-economic shift in North America at the turn of the millennium, a wealth inequality that has only increased in the ensuing decades of late-stage capitalism.

The second series in “Suburbia Mexicana” is “Lost Rivers” (2007-2009), which expands Cartagena’s inquiry to include the surrounding infrastructure, in particular the rerouted water systems and dammed rivers that made way for new housing developments. These images of erased and corroded landscapes document the effects of development on the natural environment. Together, “Fragmented Cities” and “Lost Rivers” form a sort of 21st century, Central American variation on the North American New Topographics photography of the 1970s: a deadpan look at the way suburban infrastructure has continued to ravage the continent’s landscape.

But any lived environment is nothing without the people that inhabit it. While the first two series focus on that very nothingness – empty buildings, vanishing landscapes – both “People of Suburbia” (2009-2010) (the third installment in “Suburbia Mexicana,) and “Los Americanos” (2010), turn the lens on the human. Both series offer intimate portraits of individuals and families--the first series focused on Monterey’s locals, the second on Mexicans who have crossed the border to pursue lives in the United States. In the first, people are photographed interacting with the suburban environment: in front of their homes, in cars – in one particularly striking image a man’s upper body protrudes from a hole in his front yard – while in the second series, his subjects appear inside nondescript domestic spaces, highlighting the loneliness of displacement.

In what is perhaps Cartagena’s best-known series, “Carpoolers” (2011-2012), he paints an even more intimate portrait of social space and male friendship. Each picture follows the same compositional formula: birds-eye view of the bed of a pick-up truck, where day laborers sleep or lounge on the commute to or from work. There’s something at once comforting and eerie about these pictures: gentle scenes of comradery and rest framed as cold trappings of familiar surveillance. Here, selections from the series are displayed in a grid, with two exceptions to the repetitive composition. In two pictures, we get the point of view of the car poolers themselves: a blue sky streaked with clouds. In one of these pictures, a helicopter hovers ominously in the corner of the frame. Here again, Cartagena teases the duality between surveillance and freedom, what is scrutinized and what goes unseen, the forgotten and the recorded.

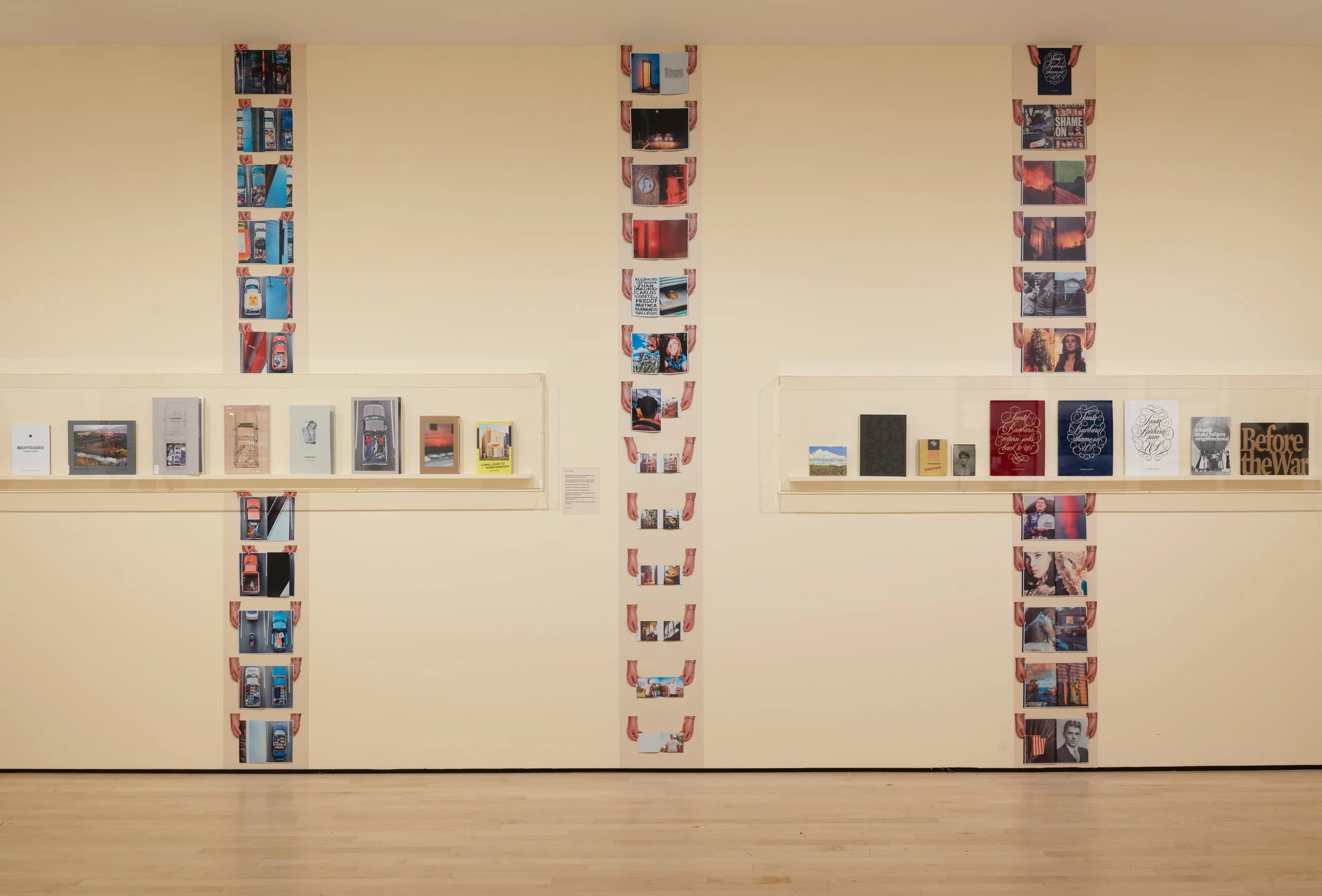

This ethos extends to Cartagena’s relationship to photography itself. The artist has published a staggering 28 photobooks over the course of his career. Not all of them feature new photographs, some instead represent old series in a new sequence or context. There are six distinct photobooks of the “Carpoolers” series and the presentation at SFMOMA is yet another remix. More recently, Cartagena has turned to collage and experimentation as a way to engage his work without actually taking new photographs.

While the results are a visual departure from his more straightforward documentary style, the conceptual bedrock remains the same-finding new ways to look at neglected things. The series “Accumulations” (2018) repurposes cut-up photos from “Fragmented Cities” in collaged grids, creating abstract continents, their source material varying in recognizability. In the delightful series “Faces” and “Family Vacation” (2017-2019) Cartagena removes, like a surgeon, the human figures from old photographs, giving a new meaning to the idea of a photographic negative. In the series “Disappearances” (2018-2019), Cartagena uses cleverly cut mat board to turn archival photographs into diptychs, the strip of board between the two windows obscuring the subject of the original image.

Here, Cartagena isn’t making the invisible visible, but rather reversing the process, obscuring what was once commemorated, in both instances, bringing a new perspective to bear on the overlooked. With the reflexive turn toward his own previous work, Cartagena’s focus shifts from the outside world to the interior landscape, the relationship not between people and place, photograph and subject, but artist and craft, artwork and viewer. It’s a reminder that nothing is wasted–one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. And what treasures they are.

Max Blue is the art critic for the San Francisco Examiner and has contributed to Artsy, BOMB and Hyperallergic, among others. His short fiction has appeared in The MacGuffin and North Dakota Quarterly, among others.

Installation view ALEJANDRO CARATGENA "Ground Rules" SFMOMA.

ALEJANDRO CARTAGENA "A small guide to Homeownership, 2020 © Alejandro Cartagena, courtesy the artist.

ALEJANDRO CARTAGENA "Carpoolers#21" 2011-12. © Alejandro Cartagena, courtesy the artist.

ALEJANDRO CARTAGENA AND RUBÉN MARCOS "Identidad Nuevo León #41," 2005–6. © Alejandro Cartagena, courtesy the artist.

ALEJANDRO CARTAGENA" "Invisible Line DAUGHTER #34", 2010–17 ©Alejandro Cartagena, courtesy the artist.