By Catherine Taylor, December 10, 2025

“How do we learn to see beyond our individuality?” asks the handwriting beneath two nearly—but not quite—identical pictures of a woman in a navy-blue raincoat with a yellow vinyl lining standing in front of a town square. The snapshots look like they were taken in the 1970s or ‘80s and are mounted to a piece of faded lavender construction paper. They are unremarkable as pictures, but curious next to the text. Do they depict the relentless proliferation of images of the self that must be circumvented? Or does their repetition aim to undermine our sense of singularity, to remind us of our banality, and thus our likeness to others? Or are they evidence of someone looking, and looking again, in an effort to understand their own singularity, its representation, and its relation to a world full of others?

The pictures appear just inside the door of the Galerie Treize in Paris and form the right-hand side of a diptych. On the faded yellow paper of the left panel is pasted a breast exam instruction sheet with the usual drawings of quadrants to palpitate. Written in the form’s name and address field: Jo Spence, 60 Leighton St. One person embedded in both a useful form of care and an unrelentingly standardized medical system. The diptych is actually an enlarged photographic facsimile of the original, laminated and attached to the wall with Velcro. The first of eleven in a row, it signals the at once accessible and complex work of Jo Spence (1934−1992), British photographer, writer, educator, activist, cultural worker, and photo-therapist, which was on view through November 22. The work is simple and smart, nuanced and direct, searing, funny, and deeply engaged in a materialist politics and practice.

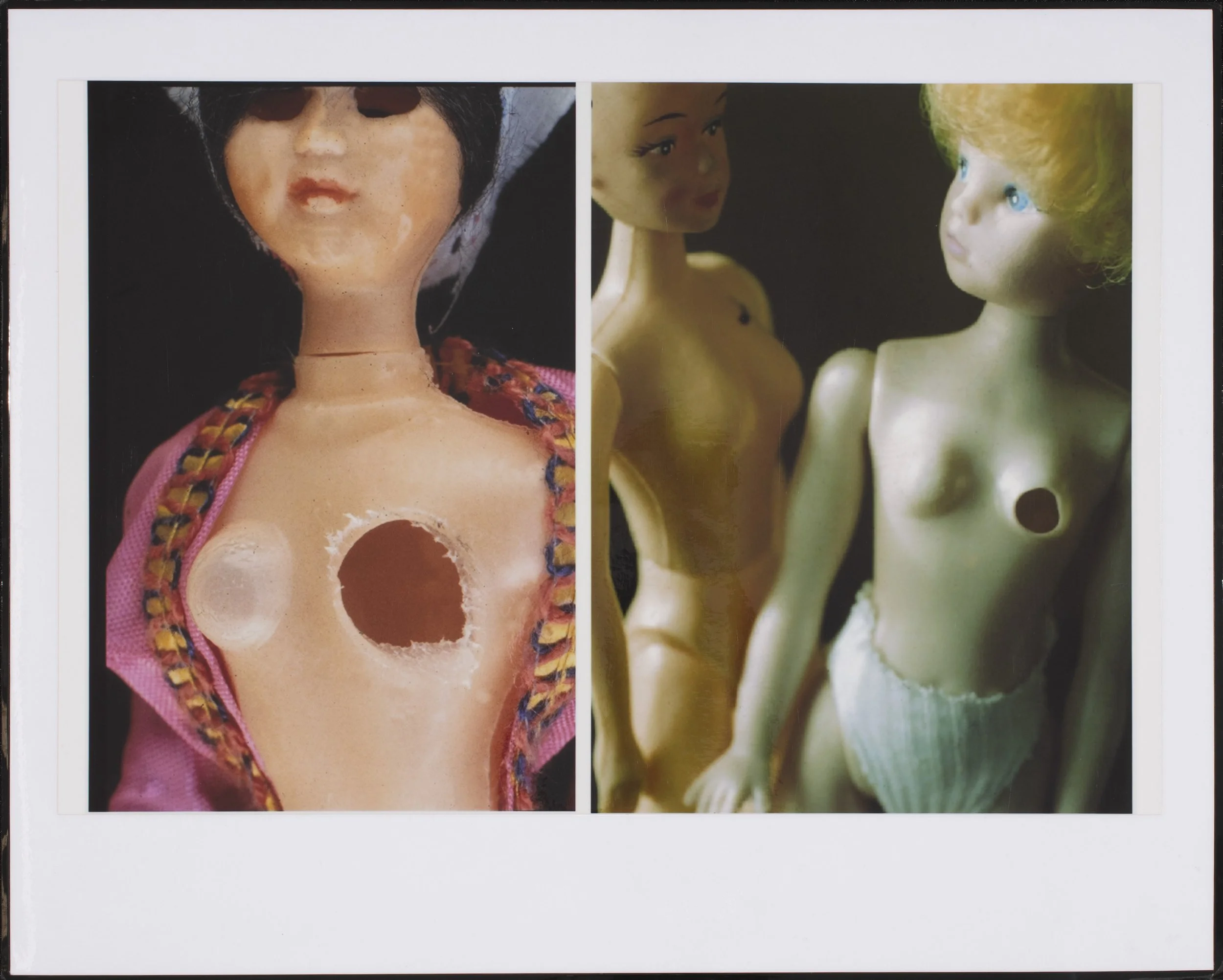

Curated by Georgia René-Worms in collaboration with Gallien Déjean and Emmanuel Guy, the exhibition features work from 1982 to 1992, the last 10 years of Jo Spence’s life, which was dedicated to the intersection of artmaking, organizing, pedagogy, outreach, and what Spence named as the heart of her work: “the question of how to represent a body in crisis.” The exhibition includes her most iconic image: a black and white self-portrait with the words “Property of Jo Spence?” written in marker on the skin of her left breast and made just prior to her surgery for cancer. The photo was created in collaboration with her then-partner Terry Dennett. Nearby are numerous other photos displaying Spence’s unflinchingly visceral and often humorous depictions of her own non-normative, “sick” body. But the real treasures of the show are the collages, ephemera, scrapbooks, and publications that make visible the collaboration, collectivity, and community work that was always central to Spence’s practice.

One table is filled with facsimiles of Spence’s critiques of the persistent myths of Cinderella under capitalism, and of the medical establishment’s advertisement of benzodiazepines as a solution to women’s labor issues. A reading area is strewn with books by and about Spence, including her “Cultural Sniping; The Art of Transgression” (1995) as well as facsimiles of handmade albums. And the space is dominated by the laminated diptychs—pages from the “Scrapbooks” series. The curatorial team selected each spread as a representation of Spence’s main methods. They include: a photo dramatization using medical professionals as actors invited to her home to re-enact the moment of her surgery; documentation of organizational work; pictures from a phototherapy session; and notes about collaboration, including one on stealing an idea from Victor Burgin. Spence was studying with Burgin in 1982, the same year she was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 48. But she was already well into her productive career by that time.

The child of two factory workers, Spence left school when she was thirteen, became a typist in a photo studio, opened her own commercial portrait studio (making wedding and family photos) and turned to political documentary photography in the 1970s, becoming a founding member of the socialist-feminist photo collective, The Hackney Flashers Collective and of the women’s photo collective The Polysnappers. Spence worked outside the world of the art market, engaging instead with community-based production and exhibition (using cheap materials easily exhibited at community centers) and collaborative creative practices focused on healing, empowerment, and social change. Spence’s photographic counternarratives led to her work with Rosy Martin, with whom she developed “phototherapy” which encouraged participants to use portraiture as a way explore and represent hidden aspects of their somatic and psychological experience. The process often involved shifting back and forth from behind the camera to be in front of it, to become both author and subject: a dialectic aimed at identity re-invention, empowerment, and improved mental health through the discovery of new ways to picture embodied selves.

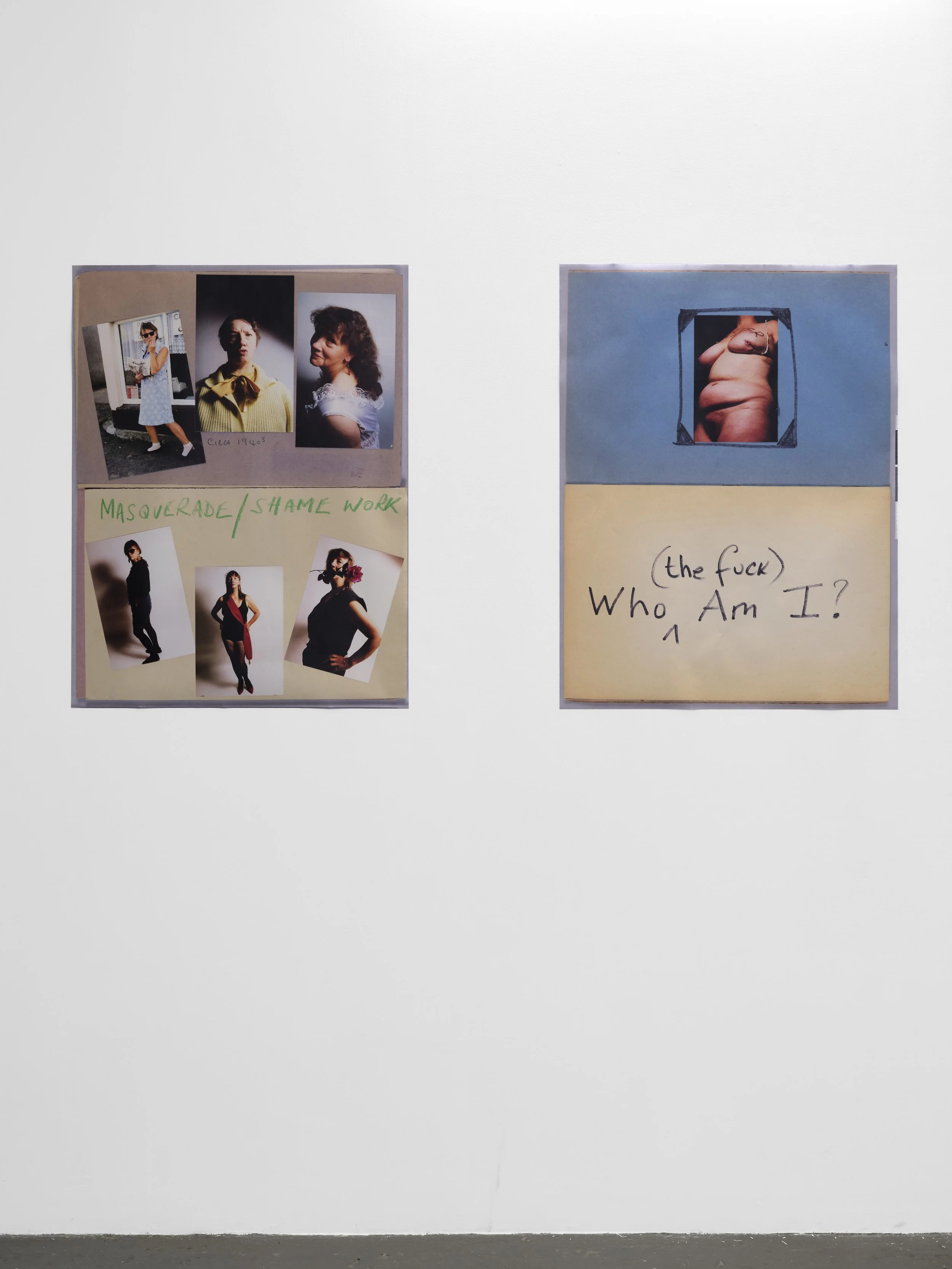

Towards the back of the gallery, some pictures are paired with questions such as: “Portrait or anti-portrait?” “How to go beyond aesthetic tricks?” “How to decide what a portrait is for?” “How to get internal permission to move on?” And finally, on the back wall, alongside a color photo of Spence’s partially amputated breast, “Who (the Fuck) Am I?” Throughout Spence’s work, the frequent appearance of text is at once didactic, poetic, and self-deprecating—part of Spence’s relentless quest to expand our narratives of self and illness while creating emancipatory image vocabularies out of pain, sickness, disability, but also vitality.

Also, at the back of the gallery (near one of two documentary films on display) is a pedestal covered with a slippery stack of prints for viewers to shuffle through; pictures of gravestones with wigs on them; goofy skull masks and skeletons in the cemetery. These photographs are part of “The Final Work”, made after Spence was diagnosed with the leukemia that would kill her. These pictures show Spence, as René-Worms says, “prefiguring death.” In looking for ways to show this new, invisible disease, Spence turned to landscapes and props as a way to allegorize death. René-Worms connects these images with the work of philosopher RosiBraidotti who, she says, “describes as the logical complement to the notion of autopoiesis: the personalization of death as a means of cultivating life through creativity.” This then supports, “counter-habits or alternative memories that do not repeat or confirm dominant modes of representation.” Flipping through the prints, René-Worms says, “I think one of the most important things in the work of Jo Spence is this question of intimacy, and for me, that becomes the question of how we can create an intimacy with the work now.” And it does feel intimate, this small, but rich, show. It doesn’t fetishize the work or bring it into a problematically commercial art world context. Neither an exploitation nor a mausoleum, the show is an active continuation of Spence’s tender, angry, prescient and engaged project.

Catherine Taylor is the author of Image Text Music published by MACK / SPBH Editions. She is a founding codirector of the Image Text MFA program at Cornell University.

Jo Spence, COURTESY OF Memorial Library Archive Birkbeck, University of London, London.

JO SPENCE "Cancer Sisters" 1982-1983. Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive Birkbeck, University of London, London.

JO SPENCE "Property of Jo Spence" 1982. in collaboration with Terry Dennett, courtesy of the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive Birkbeck, University of London.

JO SPENCE "Scrapbook 4 (14 mars-juillet 1985)", 1985. © Centre Pompidou/MNAM-CCI/Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Fonds Jo Spence.

JO SPENCE, "Scrapbook (Love me whatever I do)" 1984, SPE9, Centre Pompidou/MNAM-CCI/Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Fonds Jo Spence.