By Greg Tiani, January 10, 2026

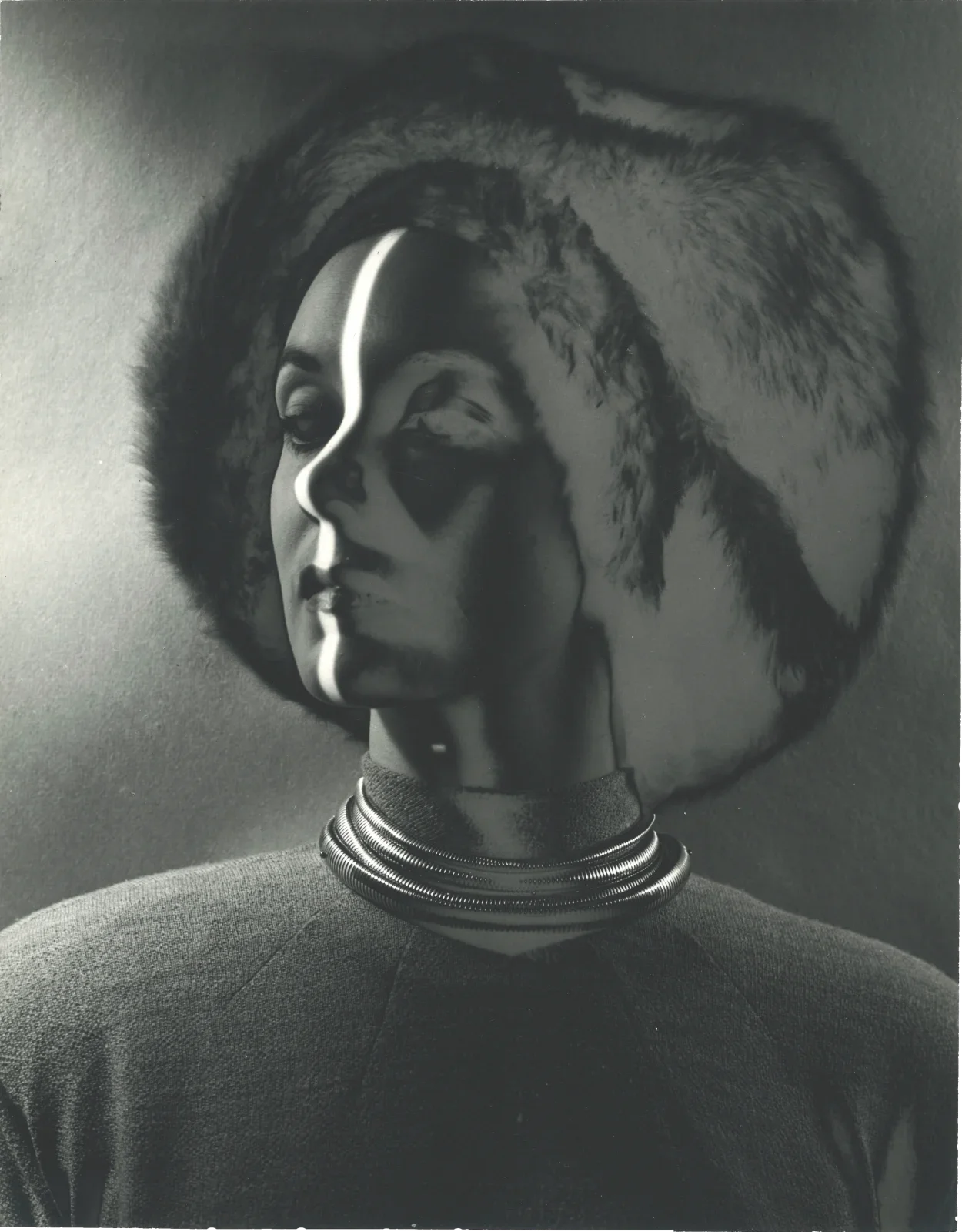

Dolled, veiled, solarised. A curious trio welcomes you at the entrance of the exhibition of vintage prints by German-born, Jewish American photographer Erwin Blumenfeld at Galerie Andres Thalmann, Zurich. Mystified, the three figures are adorned by abundant jewellery and a disquieting silence. They herald the exhibition to come.

The show offers a presentation of works which Blumenfeld produced during his Paris (1936-1941) and late New York (1955-1965) years; a slice of the photographer’s practice informed by his career as a photographer for major fashion magazines like Vogue and Vogue Paris, both positions courtesy of his friendship with British ‘bright young thing’ Cecil Beaton, and Harper’s Bazaar.

Dolled. The woman on the left, “Pearls of the Western World, New York” (1942), pulls you in with voluptuous layers of lacey brocade and overlapping strings of pearls wrapped around her wrist, neck, and escaping in loops from her right hand. Objects of luxury and desire, pearls and brocade are accomplices to the glamour already at play in the image: under the dramatic shadows created by the bright light filtering through the lace, the woman’s face is that of a smooth white plaster statue. Only the hand clutching her pearls bears an alive fleshiness.

Fashion “sculpts” the body, and Blumenfeld is keen to bring this maxim to the next level by clothing sculpture itself--- as a less than ironic proxy of the female body on display. The exhibition covertly interrogates the sometimes-problematic tension between inanimate object and the female body which Blumenfeld’s work innately holds. Around the wall which divides the room, the show introduces a diptych of a rouged mannequin and a woman similarly positioned and caught in a fishnet of Boucheron jewels (“Untitled” 1938). These images, created for Vogue Paris, make the comparison between the body and its inanimate counterpart more than a suggestion.

Veiled. The woman at the centre of the trio, “Untitled” (1938), is almost imperceptible: her face appears sketched, faded behind her veil. Only hints of her blond curls and made-up lips are visible. It is what appears to be her body, and a ballooning white fabric onto which a necklace of black beads sits unclasped, which is interesting here: as her identifiable features disappear, what is left are a deathly silence and a garment of absurd proportions.

The selection of works insists on the sculptural elements of Blumenfeld’s oeuvre repeatedly, whether through the incorporation of photographs of actual sculptures and sculptors – indeed, the main gallery includes a portrait of Henri Matisse surrounded by photographs of his sculptures, and a dissected portrait of Niki de Saint-Phalle – or by showing Blumenfeld’s idiosyncratic commercial images of figures starkly silhouetted against black backdrops and cut-outs.

Here, however, Blumenfeld’s experiment does not unfold in facile compliance to a recognisable feminine beauty canon; instead, the exhibition complicates the commercial work dotted throughout the gallery space by juxtaposing femininity to the deformation, the fragmentation, and the objectification of the female body effected by fashion and historical trauma alike. Both human and mannequin, alive and motionless, Blumenfeld’s early figures remind more of the poupées beloved by some of the Surrealists who the photographer met in Paris, than fashion divas.

Like his Dada and Surrealist contemporaries, Blumenfeld’s early interest in distorting the body may be informed by the traumatic violence of the rising threat of Nazism in the 1930s (denounced in his famous 1933 photocollage), as well as by his internments in camps in the late 1930s, which ultimately forced him to flee France for the United States in 1941. Yet, the show elects not to make this context explicit: it favours the fabled lure of fashion, while leaving the threatening stillness of the image unaccounted.

Solarised. The third woman, “Untitled” (1945), is looking elsewhere to the left. Her face, framed by a fur hat and a ravelling snake chain necklace, is split by a thin line of white light which also divides the print from the normally developed section to the inverted black and white of Blumenfeld’s solarisation, from photograph to dark bronze cast. It is unclear whether she is crystalised in her Pygmalion becoming or heading towards her sculptural immortalisation.

Both in Paris and New York, Blumenfeld would develop his black and white silver gelatin prints himself, experimenting with chemical solutions, development processes, and the overlay of multiple shots. Whichever the project, the show is insistent on the photographer’s own hands-on involvement in all aspects of his work, with solarised prints and editorial photomontages on display. Even for his commercial projects, he would methodically collaborate with editors and fashion houses to create images designed to better include the promotional overlay for magazine printing. The exhibition includes these vintage prints, still bearing the signs of the photographer’s various movements across the Atlantic.

Cleverly, the Galerie does not shy away from displaying some minor historical damage to the prints. This successfully hints at the chronological positioning of the works and participates in their thematic complexity, making up for the elision of historical context. Material bruises – a dent in the print here, a tear in the photographic paper there – are inserted in the same economy of disembodied body parts, distorted proportions, and inanimate figures. Fashion becomes articulated not only as the photographs’ mystifying smoke-and-mirrors beauty, but also through its shattering violence on form.

Demystified. The show’s introductory claims on feminine beauty should not be interpreted in the straightforward way they appear. Blumenfeld is presented here in his complexity, offering ironic and traumatic conceptualisations of beauty, which are emphasised by an appreciation of the absurd and the deadly sculptural quiet of his images.

Galerie Andres Thalmann proposes an essential Blumenfeld in all his ambivalence – one who swings between avantgarde experimentation and classical forms, between baroque lavishness and minimalist composition, between the mystifying enchantment of opulence and a traumatic historical backdrop. In addition to demonstrating the photographer’s technical bravura, all the exhibited works benefit from being not overdetermined by his more widely disseminated images.

It is only exiting the space, that one notices a small print just to the right-hand side of the glass doors of the gallery. It is one of Blumenfeld’s early works (“Untitled” 1932), before the bankruptcy of his leather goods shop in the Netherlands in 1935. An unassuming photograph of a woman posing in comparatively simpler clothes and with a significantly less experimental composition; a welcome counterpoint to the thematic grandiosity of the other images. Recognisably human, she is demystified.

Greg Tiani (PhD) is a curator and art historian specialising in contemporary photography and queer cultures. He is currently the Head of Exhibitions at Verzasca Foto and has collaborated with Centre de la photographie Genève, Fotofestival Lenzburg, and Visual AIDS, among others.

ERWIN BLUMENFELD "Untitled, Paris" 1938.

ERWIN BLUMENFELD "Untitled, Paris" 1938.

ERWIN BLUMENFELD "Untitled' 1945.

ERWIN BLUMENFELD "Untitled" 1938.