By Yael Friedman January 10, 2026

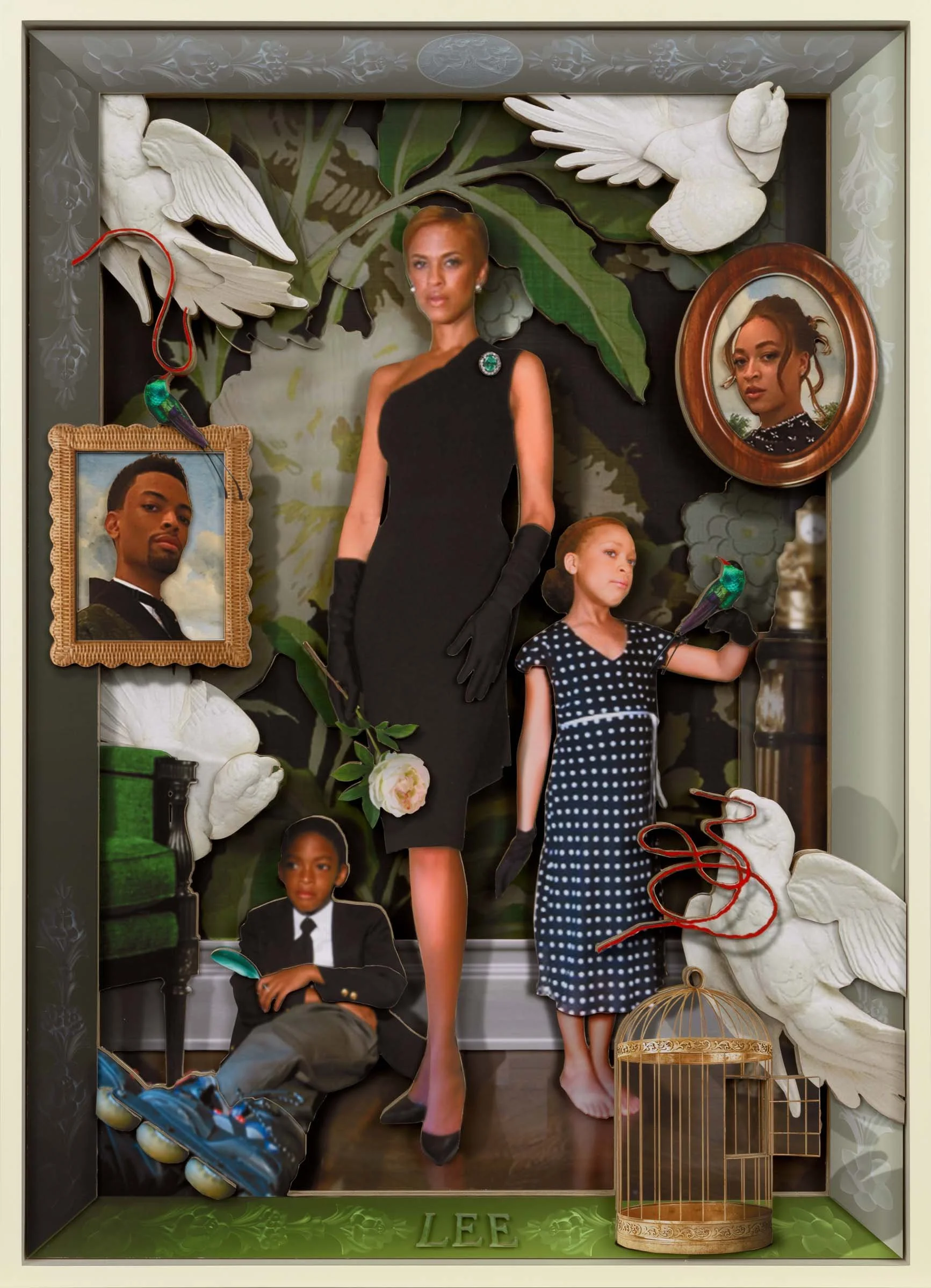

At first glance, the exuberant collages of domestic scenes in Ron Norsworthy’s show “American Dream,” seem to refute any cynicism regarding the evocative title of the show. The pictures signal the dream achieved, a material celebration of a Black middle class having arrived – large white clapboard houses, rural idylls, living rooms brimming with smartly chosen furniture, art, chandeliers, wallpaper, children watching TV and astride bicycles, adults after black tie affairs still in formal wear, resting in their well-appointed bedrooms. And yet the dress and décor recall an indeterminate recent past, a potent nostalgia evoking the dream with a heavy hand, like Don Draper’s Kodak Carousel slideshow in perhaps the most memorable advertising pitch in television history.

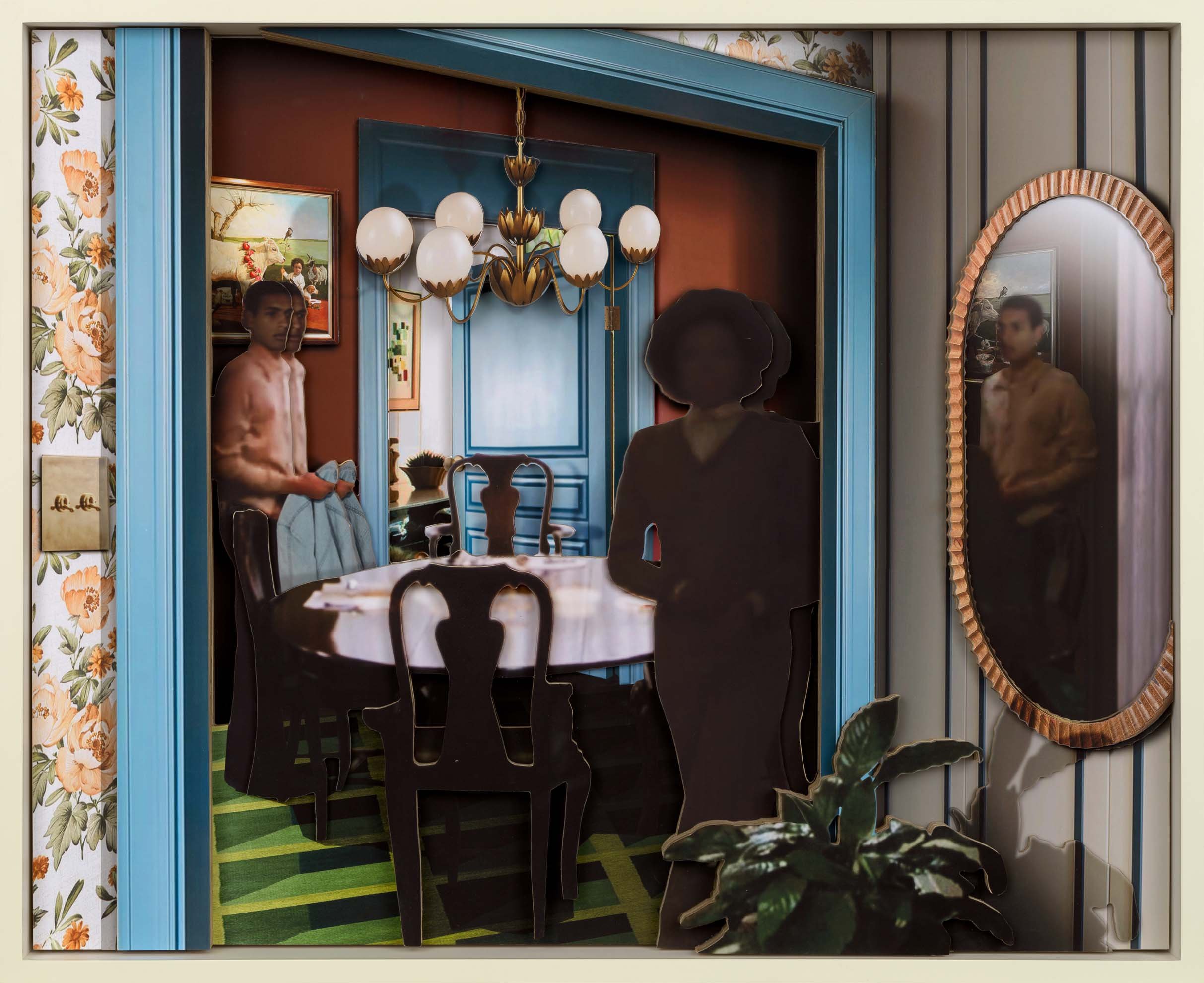

But “American Dream” does much more than give a sly wink to the hollow promises of advertising and bourgeois ambitions. Like many of Kerry James Marshall’s interior scenes, vivid colors, rich textures and a surfeit of symbols provide the setting and stage for their Black subjects, who negotiate their identities within these aspirational spaces. Norsworthy, a trained architect, spent many years as a set designer, and his masterful understanding of place, and how one defines oneself through it, is on full view here. Home ownership remains one of the most definitive symbols of American middle-class success; how one chooses to cultivate that space, and live within it, reflects one of the greatest projections of aspirational identity, the kind that one seeks to sincerely inhabit, not merely pretend to.

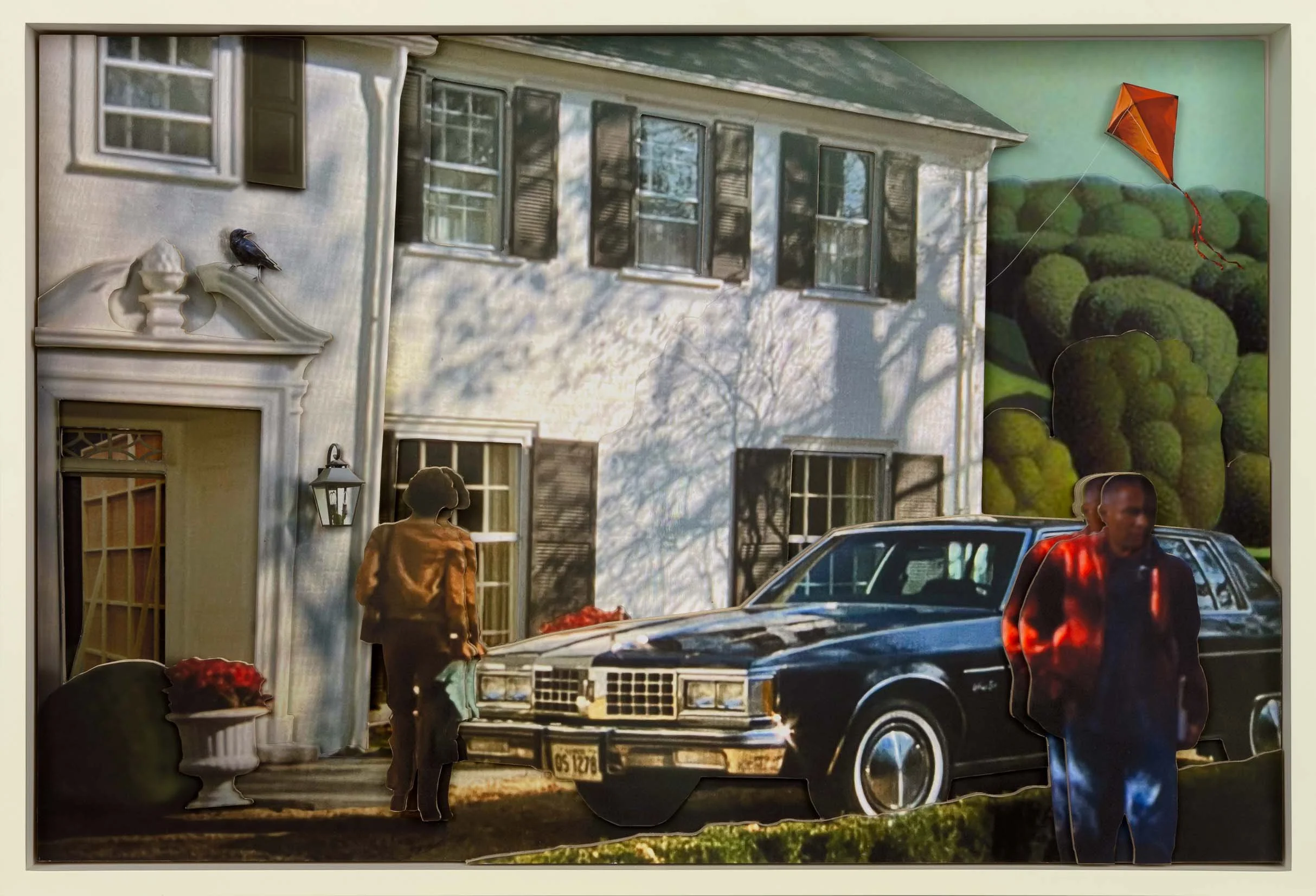

Norsworthy’s compositions complicate these “Illusions of Eden” as Marshall once called them, through rich layers of uncannily familiar images and meanings. And they are only effective because of how seductive they are. Built from collaged photographs mounted onto plywood, each section is then cut and built out to follow the contours of the different elements. The exposed plywood edges make the construction visible, each element and reference clearly defined and grafted onto the next. The result is a dazzling sculptural tableau consisting of photographs culled from auction catalogues, personal photographs, wallpaper designed by Norsworthy, film, and the annals of art history. The white house in “Coming and Going” is the house from the movie “Ordinary People.” If one looks closely enough, through the door, it is just a façade, the set of an already haunting and devastating story of a hollowed-out family living inside a perfect house. If one looks closer still, the two figures in it are blurred, and are either coming or going. In fact, in almost all the canvases the figures are not looking at one another.

Ambiguity and alienation permeate all these canvases. The framing is often slightly askew, the architecture, the cars, the most intimate scenes, are cut off at odd angles, and mirrors often add another portal to the narrative – often including the image of Norsworthy himself. The fourth wall is broken often, because of the compositions’ spatial entry into our experience of these seemingly two-dimensional canvasses, the direct gaze of some of the subjects, and the wry inclusion of the reflection of the photographer.

Norsworthy’s beautiful intrusions into these domestic spaces also calls forth the “battleground of the national family album,” as Deb Willis describes it in Thomas Allan Harris “Through A Lens Darkly”. Black photographers have not only had to reclaim the images of African Americans, whose depictions were in the hands of white photographers, they have had to add to a severely incomplete and distorted vision of the American family. As Harris remarks in his film, “There is one place where all the secrets reside, in the family photo album and what it chooses to represent, and what is absent, hidden.” Norsworthy has taken the family album and enriched and complicated it further, allowing a rich articulation of the difficulties of negotiating identity, of embodying oneself in the material world.

Yael Friedman lives in New York, and her reviews and essays have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Economist, The Forward, Haaretz and The Daily Beast, among other publications.

RON NORSWORTHY "Do You Know What You're Looking For?" 2025.

RON NORSWORTHY "It's Been A Day" 2025.

RON NORSWORTHY "Trying To Remember The Future" 2025.

RON NORSWORTHY, "Tonya Lewis Lee And Children" 2005-2025.