By Jean Dykstra, January 10, 2026

The luminous Seydou Keïta exhibition on view through May 17 at the Brooklyn Museum includes nearly 300 works by the late Malian portrait photographer, who died in 2001. Organized by guest curator Catherine E. McKinley, “A Tactile Lens” concludes with a room devoted to the patterned textiles Keïta regularly included as backdrops in his photographs, as well as mannequins in traditional Bamako dresses and vitrines with elaborately crafted gold ornaments and jewelry. An accompanying soundtrack by American musician, producer (and founder of Chic) Nile Rodgers and Malawian DJ Chmba Chilemba pulses quietly throughout the exhibition.

These curatorial choices enrich the experience of viewing Keïta’s portraits, but they also situate them within their rich and complicated cultural context. Keïta’s photographs, made between the 1940s and the 1960s, were taken as the country was moving toward an inflection point: in 1960, Mali gained independence from France, one of 17 African countries to end colonial rule. It was also a period that saw a large migration of people from rural areas into the cities, and many of them wanted photographs taken to send back to their families. Unlike colonial-era photographs of West Africans, Keïta’s portraits were deeply collaborative projects in which the subjects performed aspirational versions of themselves or used the portraits to commemorate marriages, births, and other events. Many reflect a casual physical intimacy, arms draped across shoulders, hands clasped, sitters hip to hip.

“As a colonialist project,” writes Howard French in the accompanying catalogue, “photography recorded the subjects, landscapes, customs and possessions of the colonial state. But studio photographers across Africa and India were instrumental in subverting the colonialist gaze where they gave authorship of the photo back to the subject.” Keïta’s self-possessed, beautifully dressed subjects, posed in front of patterned cloth backdrops, gaze directly into the camera and out at the viewer. They wear flowing, patterned textiles (or, on occasion, suits) and incorporate various props on hand in the studio: a radio, a bicycle, a Vespa, a fountain pen, plastic flowers, as well as jewelry, signifiers of status. In one well-known and wonderful photograph, a fashionable young man in a white suit and tie has a floral pocket square and a pen tucked into his suit pocket. He wears chunky glasses and a watch and holds a single plastic flower. Even one of the most minimal photographs in the show – printed oversized here – shows a woman in a room that’s bare except for the strips of film hanging on a line behind her; she wears a simple sleeveless dress but also magnificently high platform sandals.

Traces of the culture and fashion of French colonialism are threaded throughout the images. Posing in front of a fringed, patterned cloth, a boy with a somber expression rests his hand on a bicycle, wearing a rakish-looking beret, for instance. In another photograph, a young woman resting her chin demurely on her folded hands, multiple bracelets around her wrists, wears a head scarf folded in a manner inspired by the hats of French female soldiers. The influence of nearly 70 years of colonial rule is pervasive, but Keïta’s photographs suggest the many ways his subjects translated those influences and incorporated them into their own styles.

Keïta was self-taught, but he apprenticed with Malian photographer Mountaga Dembélé, eventually taking over his studio. As his reputation grew, his subjects included not only people from Mali, but from Senegal, Mauritania, and Benin as well. He made small vintage prints for his subjects, which they used as identity cards, keepsakes, or mementos, some of which have hand-painted details, including colored bits of jewelry, headscarves, or a painted red lip. These are included in the exhibition, along with the large, high-contrast prints (roughly 22 x 16 in.) made in the 1990s, after he was “discovered” by European and American dealers and collectors.

Keïta had to close his studio in 1963, when he was drafted into government service as a photographer by the newly independent Malian government, and when he returned home in 1977, his studio had been ransacked and his equipment stolen. He retired as a photographer and worked as an auto mechanic, but in 1991, several of his photographs were included, unattributed, in a group show at the Center for African Art and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, where they were spotted by the collector and socialite Jean Pigozzi, who sent his curator, André Magnin, to Mali. Magnin tracked down Keïta as well as the younger Bamako photographer Malick Sidibé; he brought back 921 of Keïta’s negatives and made prints for a show at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, which led to a show at Gagosian, among other places, a 1998 cover on Artforum, and a market for his work in Europe and the US. There was reportedly some acrimony between the photographer and Pigozzi and Magnin toward the end of the Keïta’s life, but almost half of the works on view here are on loan from Pigozzi; others come from Magnin, Keïta’s family, and other institutions and private collections. The Keïta estate is represented today by Galerie Nathalie Obadia and the Danziger Gallery. While the history of the market for Keita’s work is complicated (and not unencumbered by the baggage of colonialist appropriation and valuation of non-Western art), it also speaks to the disconnect between the value of the small vintage prints made by Keïta for the individuals who posed for him, prints which accrued signs of wear and handling, and the value assigned the larger, “cleaner,” prints by the art market. Keïta himself loved the look of the larger prints, telling curator Michelle Lamuniere that when he first saw those larger prints, “I knew then that my work was really, really good.”

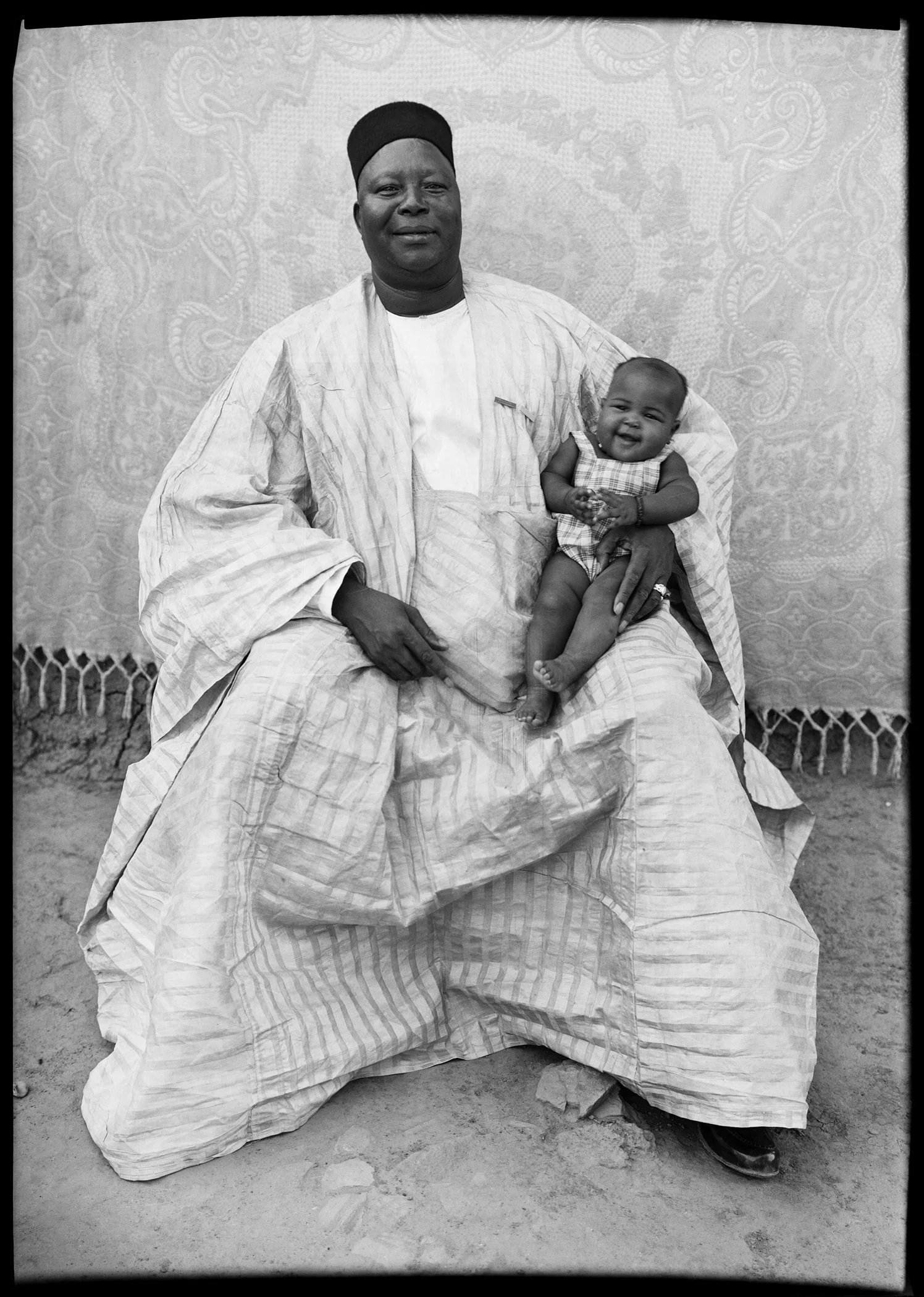

Those prints do, indeed, illuminate just how good Keïta’s work was, but the smaller, vintage prints – the original iteration of his negatives – have a certain magical quality to them, with their torn edges, spotting or staining: marks of their journey from Keïta’s studio into his subjects’ homes or wallets, the traces of being passed from hand to hand. Having a portrait made was an occasion, and many of Keïta’s subjects are accordingly solemn in their expressions and formal, often regal in their poses. One of my favorites, though, shows a large man in flowing robes, a baby nestled into the crook of his elbow, both relaxed, both with the same smiling face. The man is self-possessed, joyful and proud, and the beaming infant embodies a possible future in a country that is rapidly changing and redefining itself.

Jean Dykstra is an editor and critic and has contributed recently to the New York Review of Books, Dear Dave, magazine and The Brooklyn Rail. She was the editor of photograph magazine from 2013-2024.

SEYDOU KEÏTA "Untitled" 1948-63. The Estate of Steven C. Dubin Courtesy the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery.

SEYDOU KEÏTA "Untitled" 1949-1951 Courtesy the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery.

SEYDOU KEÏTA "Untitled" 1957-1960. Courtesy the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery.

SEYDOU KEÏTA "Untitled" 1957. Courtesy the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery.

SEYDOU KEÏTA "Untitled" 1959. Courtesy the Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery.