By Tom Cugliani, February 10, 2026

For most people, creation is associated with life. For Alison Rossiter, it is from death that the creative process takes life.

While this dynamic can invoke a spiritual understanding of the cycle of life, death and transmigration, this paradigm seems absent in Rossiter’s work. As an artist however, she is in the business of transcendence. By deliberately choosing materials that have long since extended past their expiration dates, the artist has re-activated their usefulness with new life. This is done as much with exhaustive chemical inquiry as with the development of a bespoke skill set particular to her darkroom practice.

Rossiter’s investigation into the history of photography runs parallel to her use of expired papers in her practice. There has been much reported regarding her archive of collected photographic papers, some of which date to the mid-Nineteenth century, and of the patinas that are evoked through their exposure at a distance of 100+ years. However, it is not only Rossiter’s ability to animate life by exhuming the bones of history that distinguishes her – it is her reverence, on one hand, and her resistance to convention on the other that opens a channel of exploration to create out of familiarity, something refreshed and new.

Historically, the ability of photography to register a “real truth” challenged the hegemony of Nineteenth century painting and sculpture. As a result, it was dismissed as a fine art practice and sidelined instead to industrial and commercial applications. Only in recent decades has photography been credited as a fine art force propelled into the Modern era and leaving an irreversible imprint through its unique contributions.

In Rossiter’s current exhibition through March 14, “Semblance” at Yossi Milo Gallery, the artist has positioned herself both at the birth of photography by invoking Louis Daguerre and Leo Baekeland’s innovations in the European mid Nineteenth century, and at the birth of Modernism in the first decades of the American Twentieth century through engaging Man Ray.

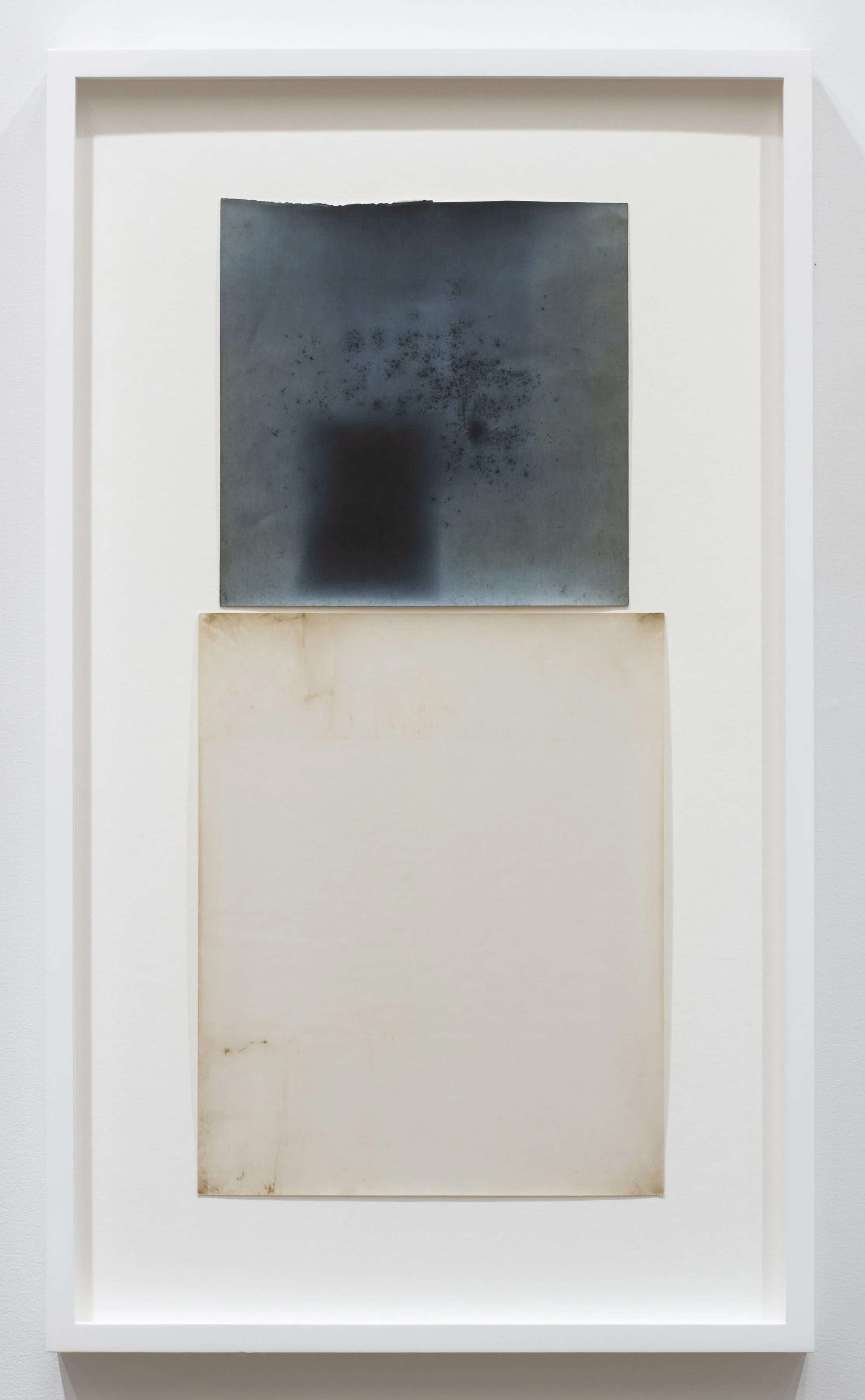

In her series “Daguerre Baekeland” Rossiter has resurrected expired plates of silver daguerreotypes, paired with the chemically sensitized papers pioneered by Baekeland to create vertically stacked compositions. They summon the paintings of the Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko. Whether intentional or not, the inference here places photography at the root of the genealogical tree of Modernism. Rossiter’s narrow choice of composition for “Daguerre Baekeland” is a repetitive juxtaposition of the mirrored surface of silver over the opaque field of tone, evoking a vision of artistic dichotomy, with one aspect being reflective and external and the other self-reflexive and internal. Aesthetically refined and beautiful, these intimately scaled pieces invite contemplation. The watery light-shifting silver plate recalls atmospheric mutability while the opacity of the stained paper conjures earthiness, sand, dust. This elusive condition of reflection and substance has captivated many artists, notably Claude Monet whose Impressionistic Nymphaeas dislocate at the confluence of air, and water and the land; not dissimilar to the way the work of California Minimalist John McCracken playfully dissolves the borders of object and reflectivity one hundred years later.

Despite a temptation to perceive Rossiter’s compositions superficially as landscape, reading them as elemental gives them a more meaningful dimension. In the duality of the immaterial and the tactile, the masculine and feminine, intellect and natural we understand how these themes are the timeless threads that hold together the creative imagination. By vertically stacking the composition, Rossiter is asking us to consider these works in the context of Rothko – of Modernism - in which a reductive arrangement of shapes enhance the elements of color and edge to create a portal through which we enter an elevated conscience.

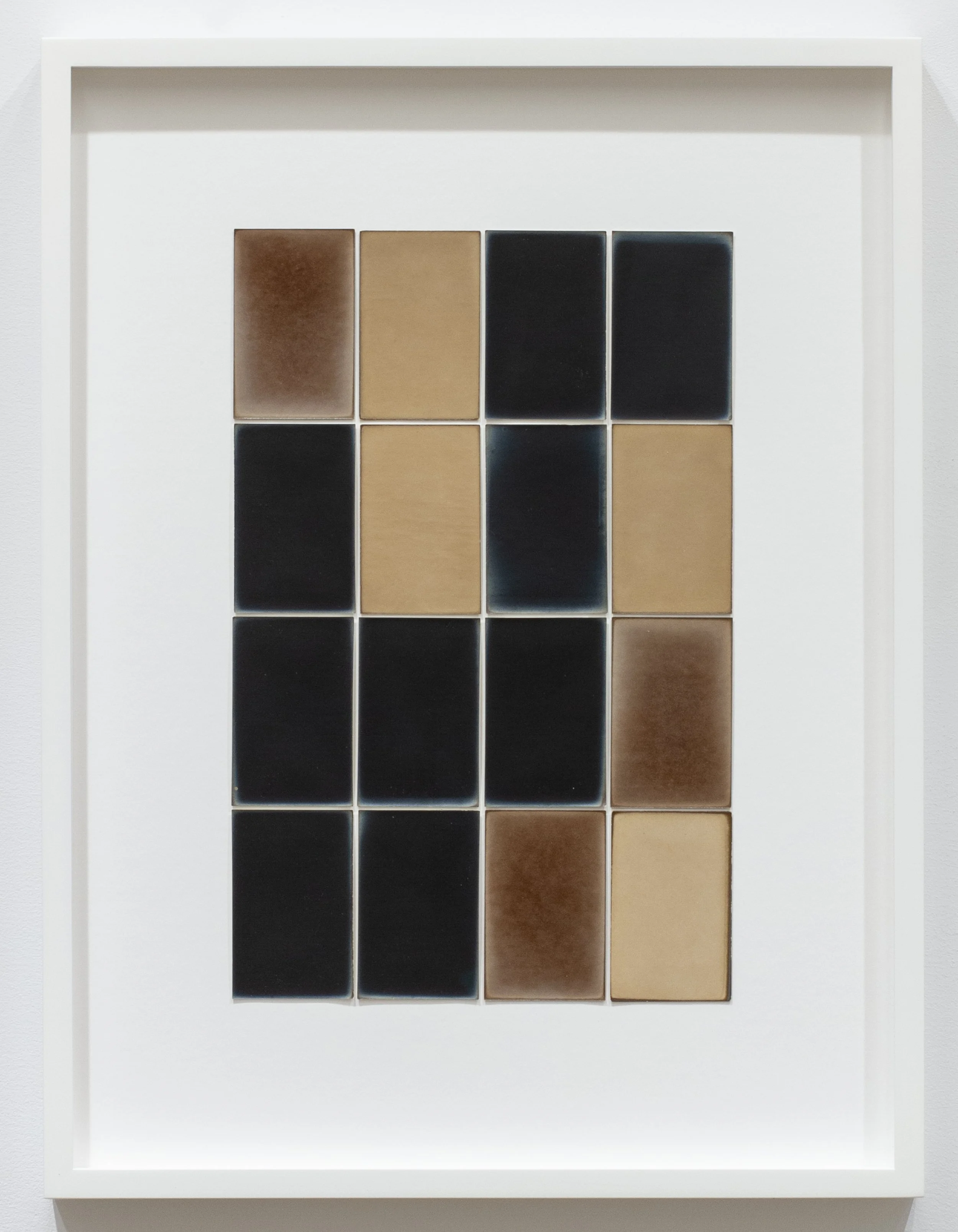

In “Semblance, Man Ray Tapestry” Rossiter debuts a series of multi-paneled pieces that take inspiration from the early Man Ray piece “Tapestry” from 1911, a work composed of same-sized square fabric swatches sewn as a patchwork quilt (or grid) and hung like a painting. Here, Rossiter has recreated multiple variations of the textile squares using vintage gaslight papers from the 1920’s, which through careful chemistry and handling in their exposure to light render a nuanced array of tonalities ranging from very light to opaque.

“Semblance” is an exhibition of similarities, ones that may be manifest superficially yet make up our collective DNA. Like family resemblances among siblings or inter-generations, they are the markers that determine our traits and also allow for our deviations – innovations, and happenstance from which new narratives are born. From antiquity to the radical innovations and serial inventions that have delivered art to this digital age, Rossiter seems to be saying that it is all of a piece. One inherited thread that in fact never expires, never dies out completely. Even at the End there is a Beginning.

Tom Cugliani is an art dealer, curator and advisor. Since 2024, he has been the curator of Sculpture@Sylvestor Manor, a seasonal exhibition of outdoor sculpture on Shelter Island, New York.

ALISON ROSSITER "Eastman Kodak, Azo Hard E, expired September 1919, processed 2018", 2025. © Alison Rossiter. Courtesy Yossi Milo, New York.

ALISON ROSSITER "Semblance, Man Ray Tapestry 1", 2025. © Alison Rossiter. Courtesy Yossi Milo, New York.

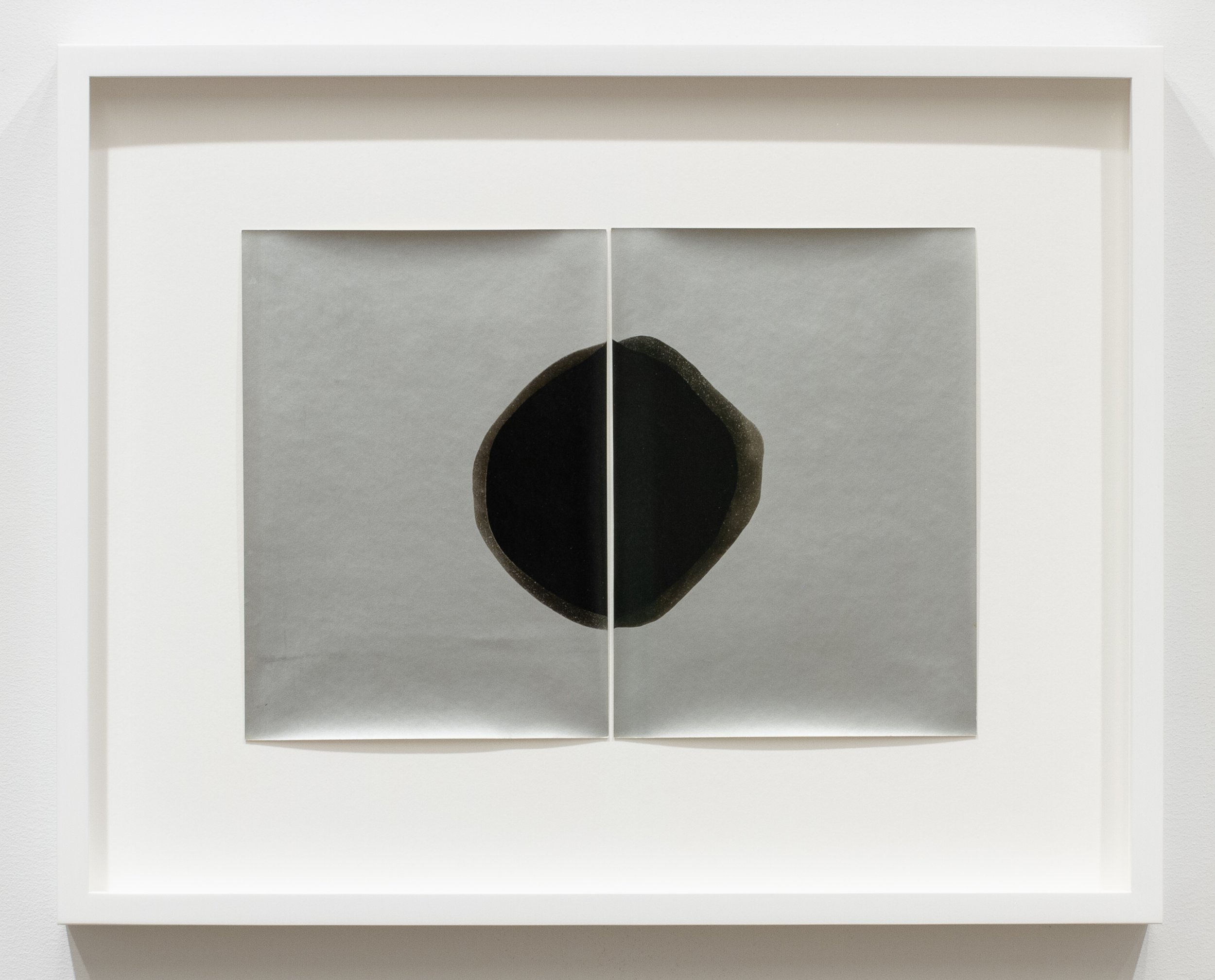

ALISON ROSSITER, "Silvered Darko (Sears Roebuck & Company), exact expiration date unknown ca. 1900s, processed 2016”, 2025.

© Alison Rossiter. Courtesy Yossi Milo, New York.

ALISON ROSSITER “Guilleminot-Boespflug & Cie, Etoile, ca.1930s / Gevaert Larjex, ca.1950s” 2025. © Alison Rossiter. Courtesy Yossi Milo, New York.